Cameron Rowland

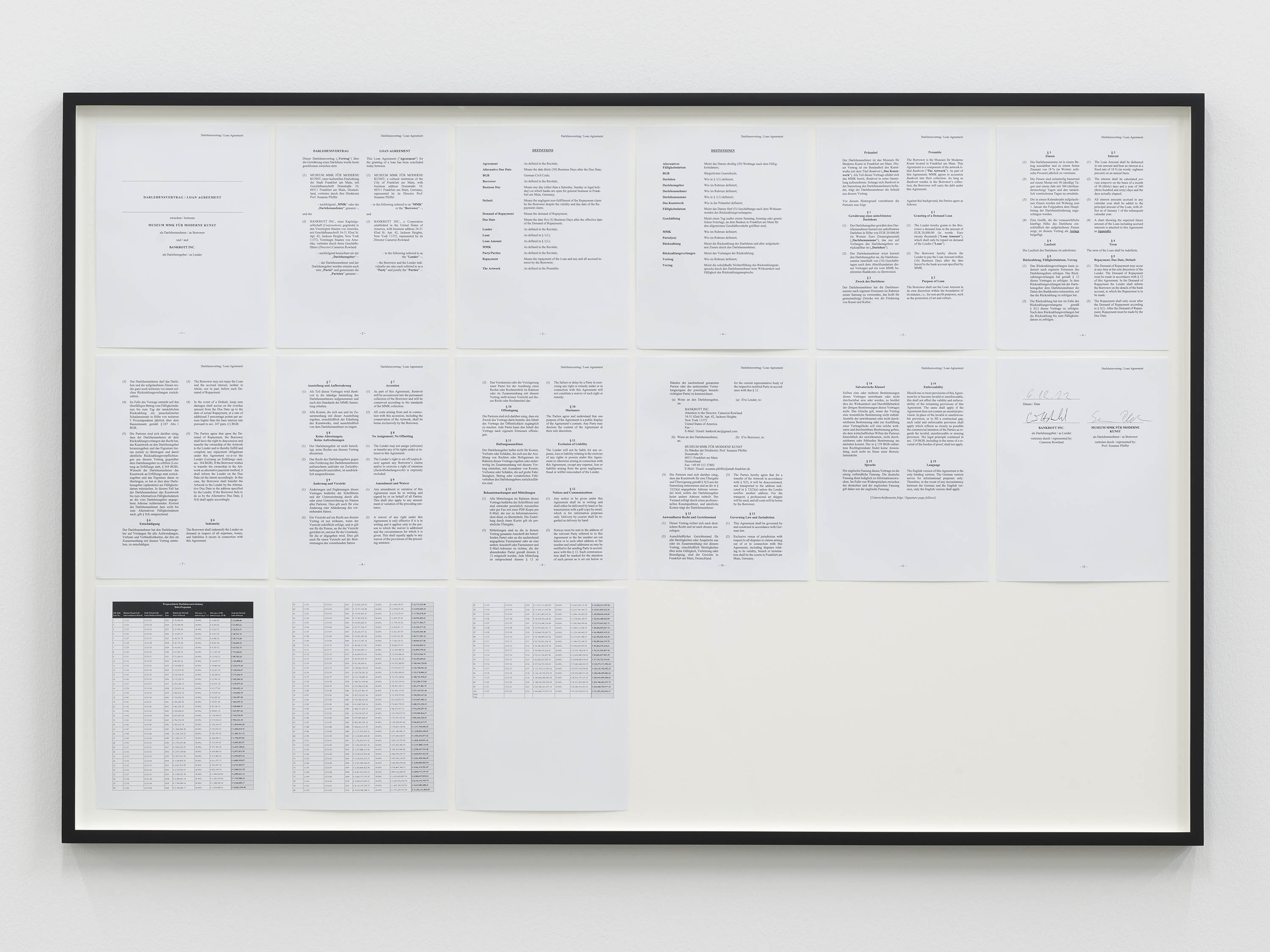

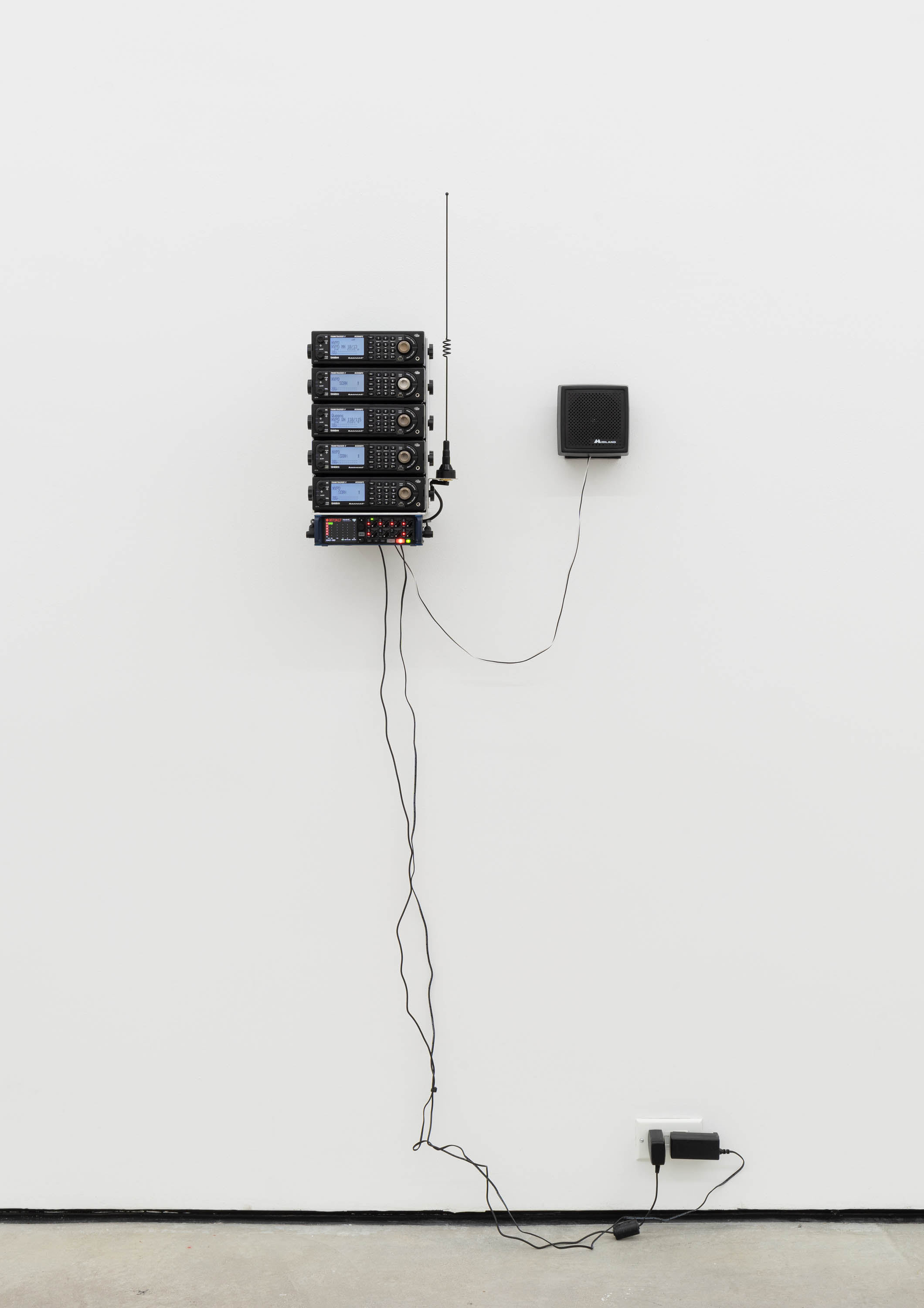

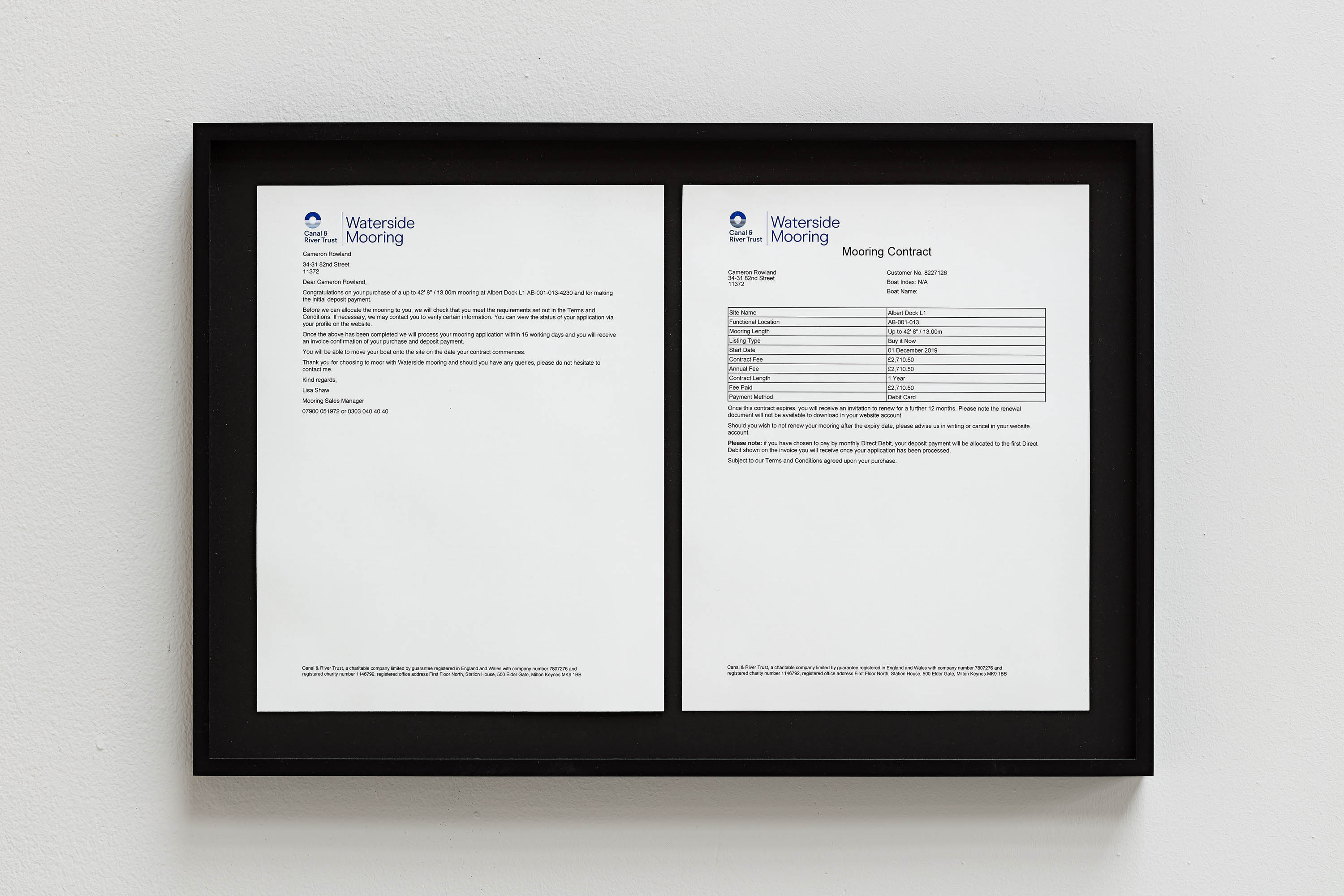

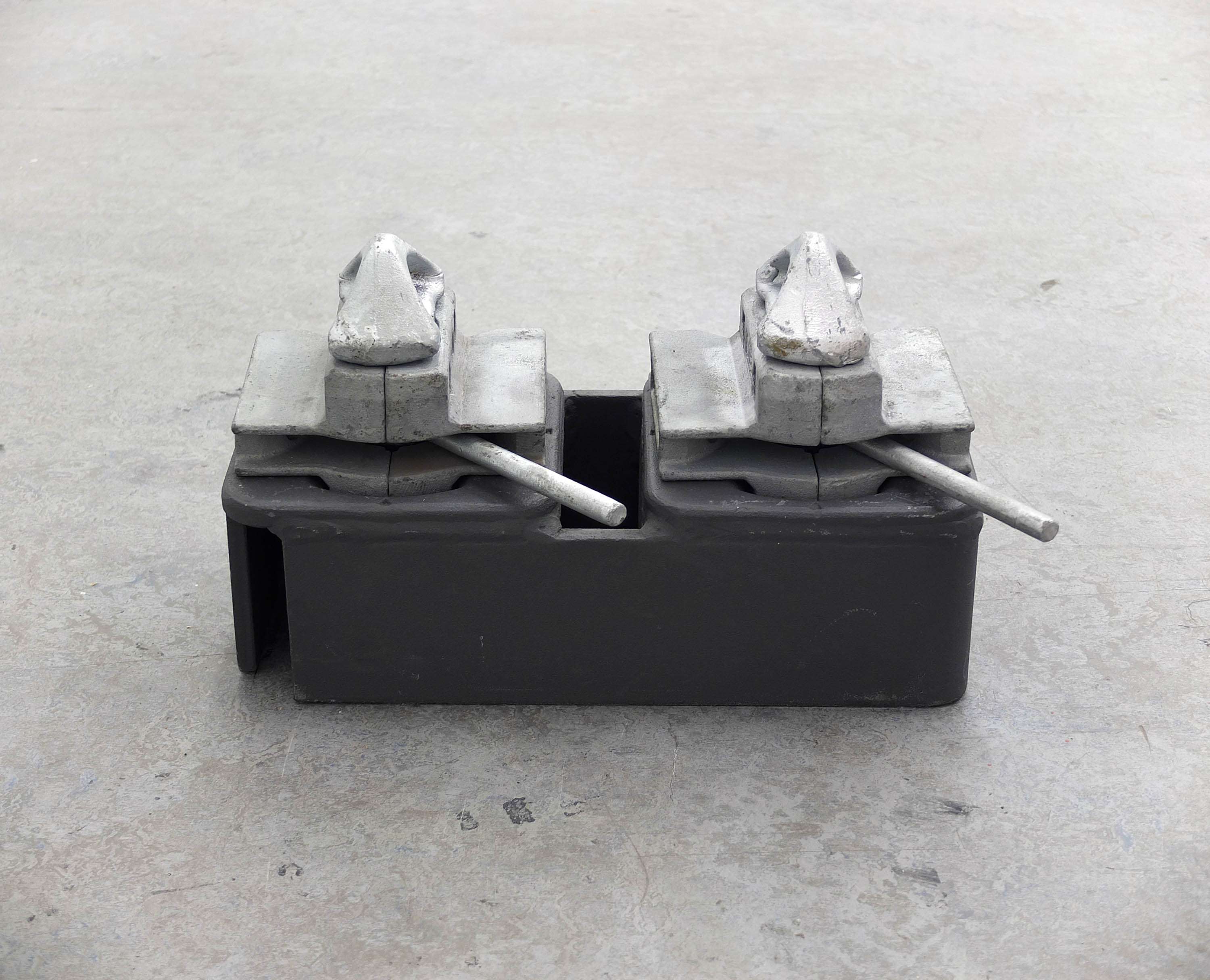

Public Money, 2017

Institutional investment in Social Impact Bond

Social Impact Bonds marketize social services and their recipients. As instruments of austerity, they structure shortterm, privatized social services as investment opportunities to reduce government spending. Detailed information on Social Impact Bonds is limited to investors. As they are sold through private placement, investors must be invited to participate.

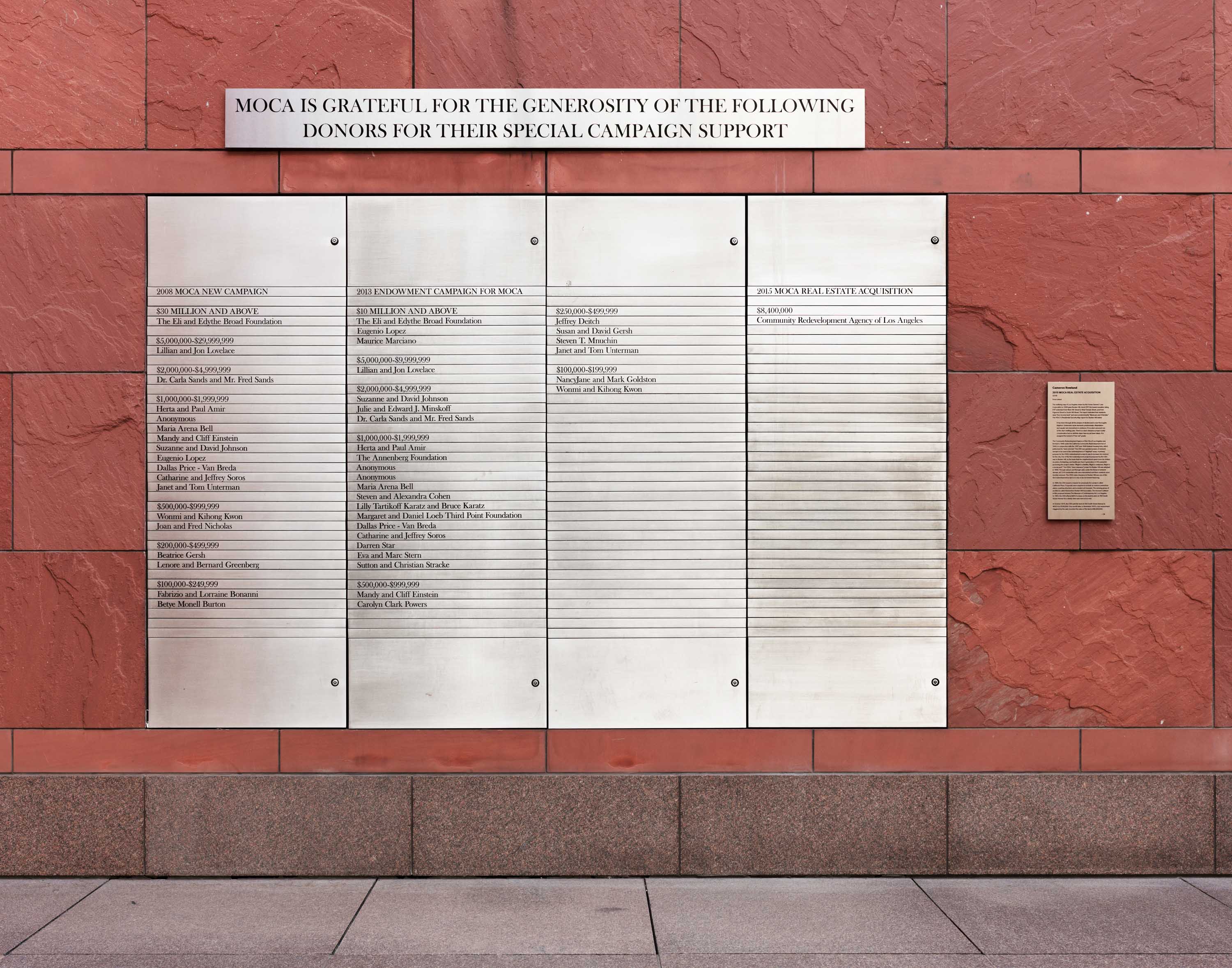

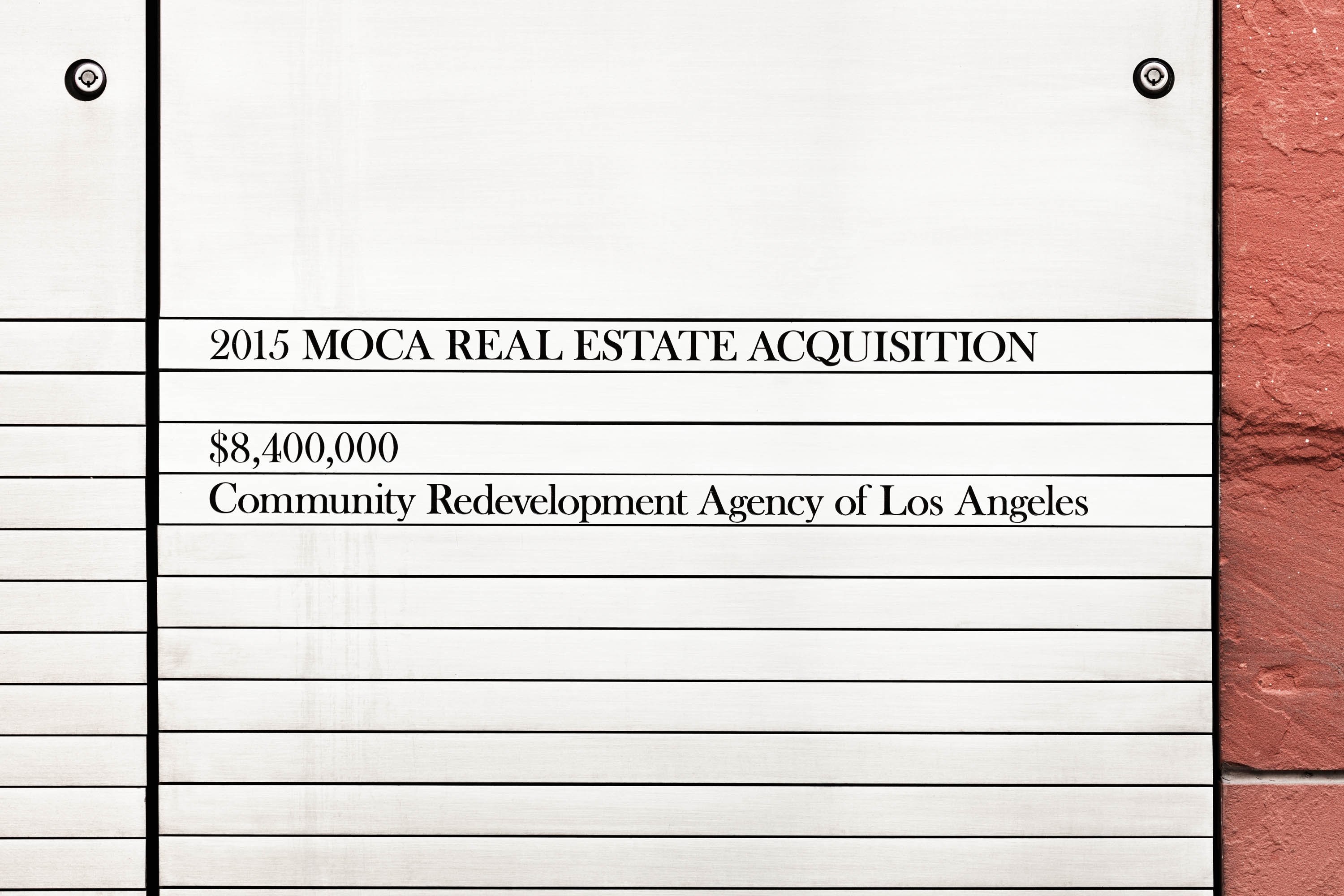

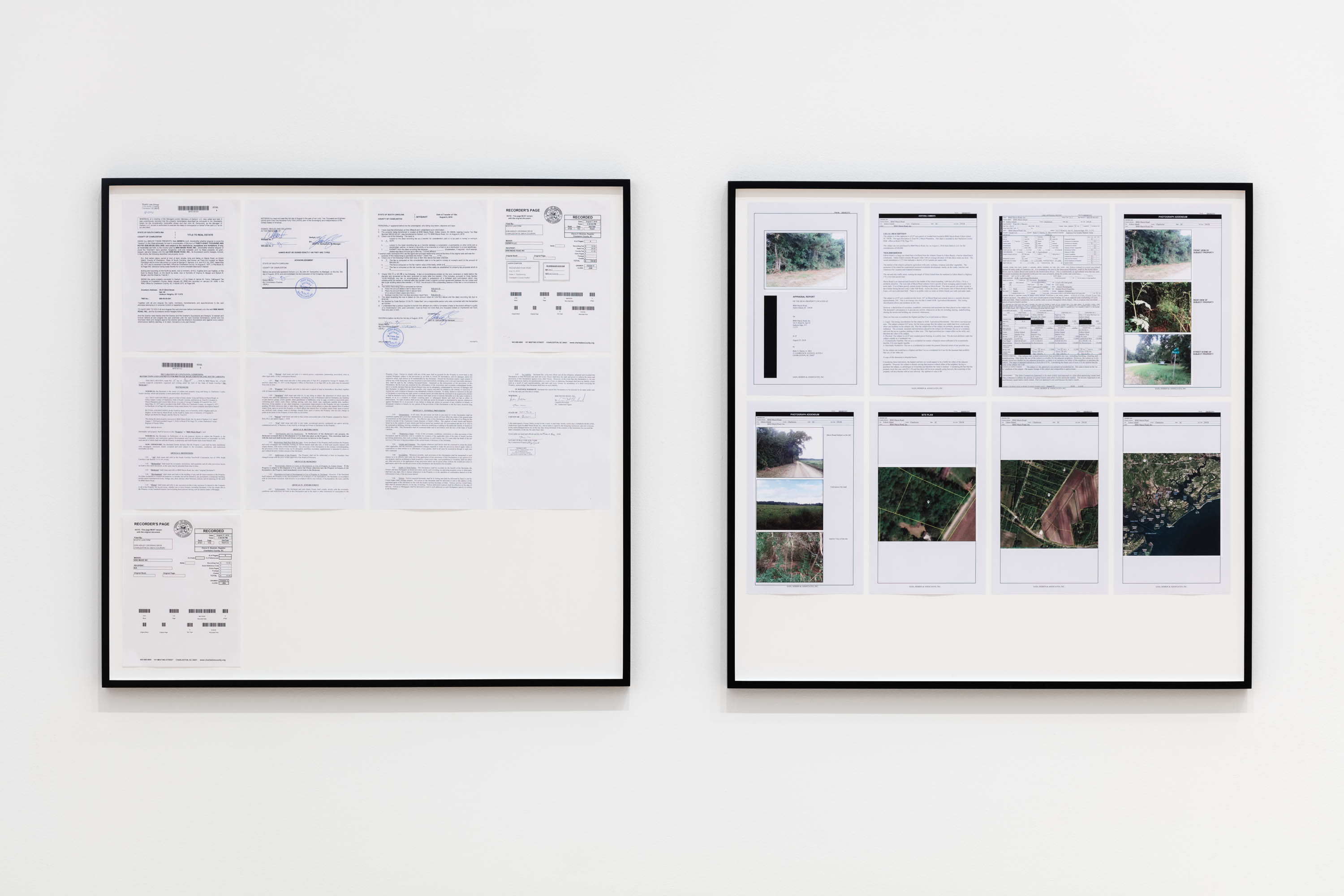

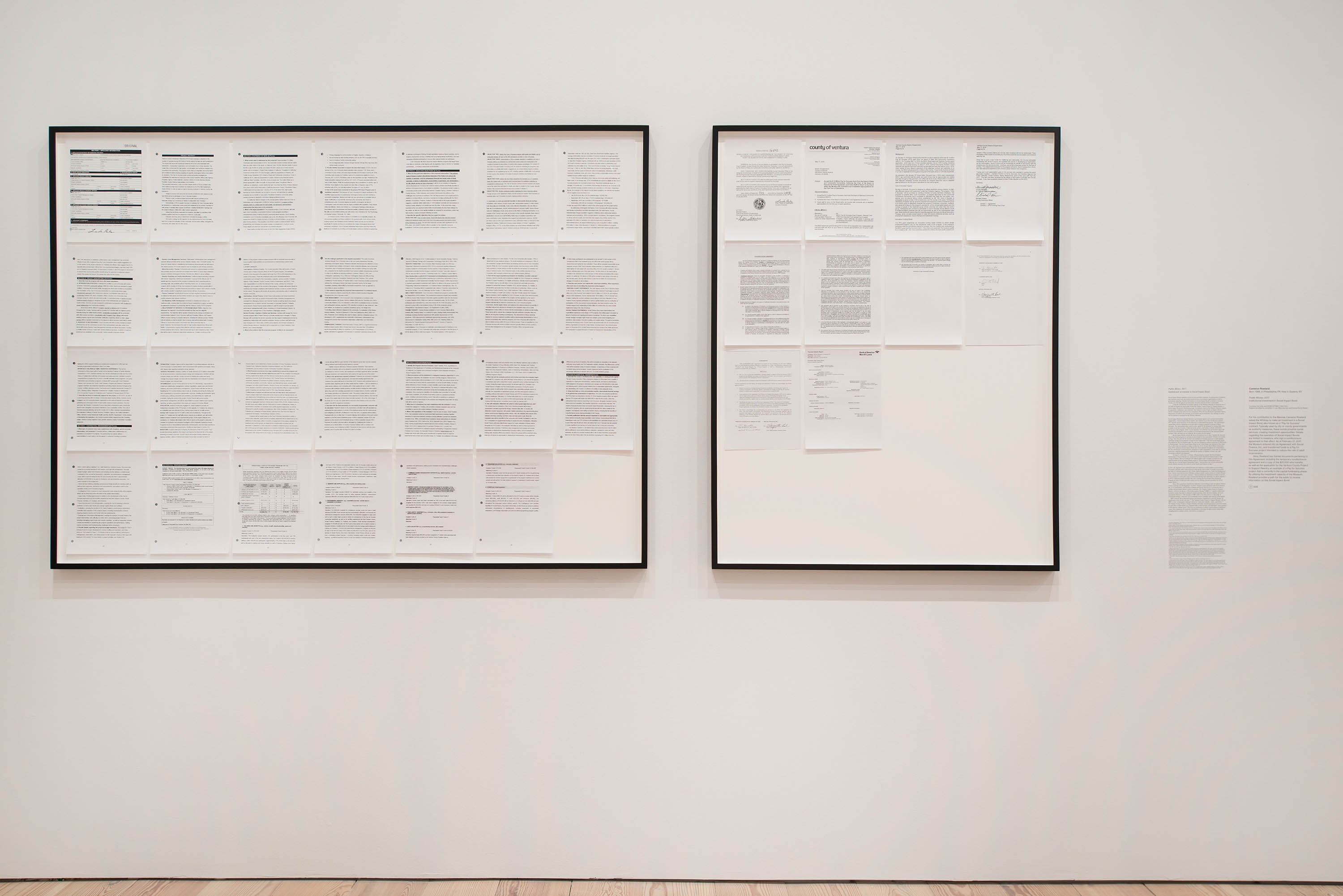

Using the institutional investment capacity of the Whitney Museum of American Art, a $25,000 investment has been made toward the Ventura County Project to Support Reentry, a Social Impact Bond in its fundraising stage. Investments made by the Whitney Museum support its operations, exhibitions, and collection. The Ventura County Project to Support Reentry will be evaluated at the end of its five-year period. When the non-disclosure agreement expires, information provided to the museum as an investor may be disclosed. Any earnings or losses will be retained or sustained by the Whitney Museum.

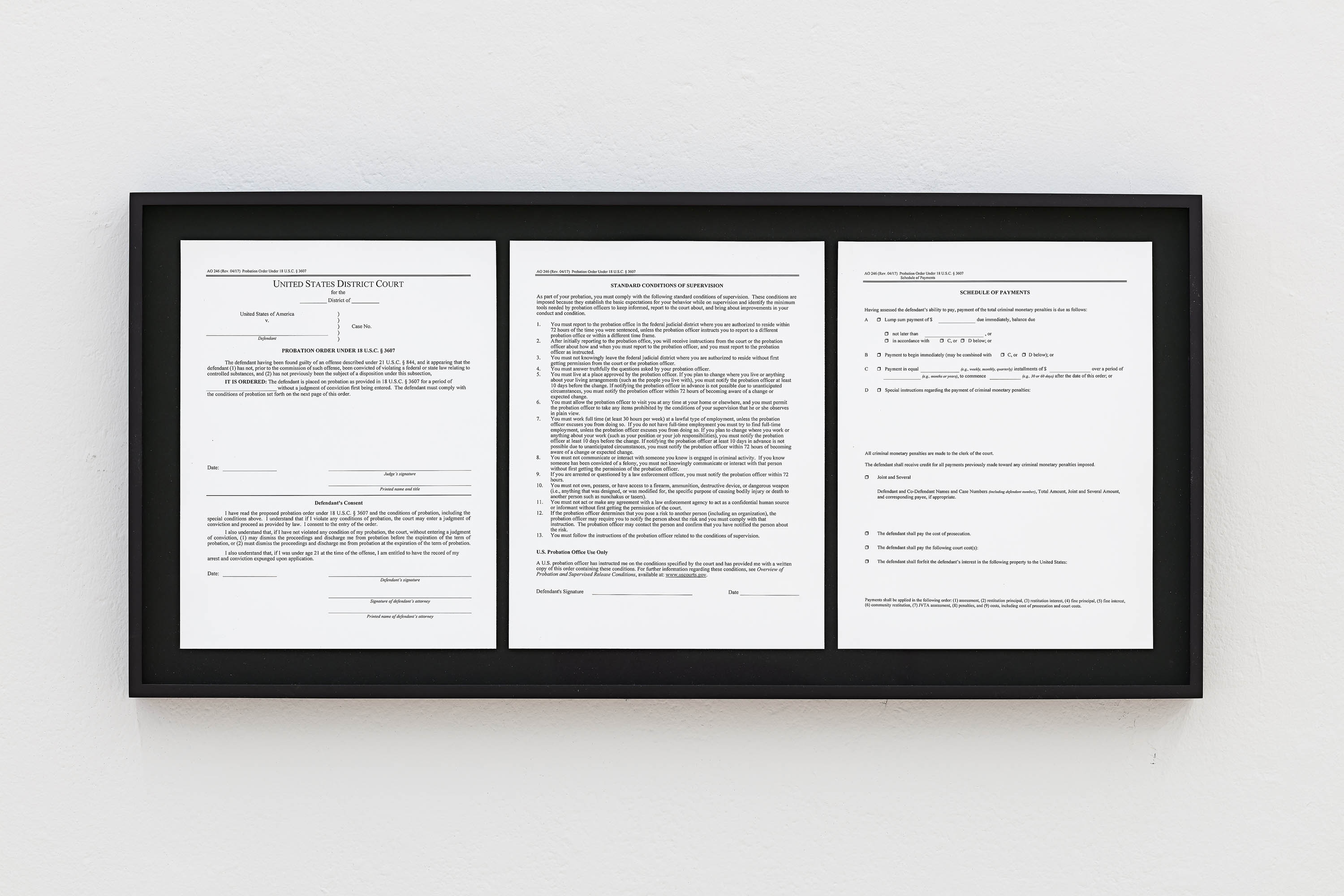

Social Impact Bonds are initiated between a government agency and a private intermediary organization. A Social Impact Bond contract, also referred to as a Pay for Success contract, sets “specific social outcomes” to be achieved in a determined time period.1 The intermediary organization selects a nonprofit service provider to design a program in pursuit of those outcomes. The intermediary then works to raise capital for the program by issuing either debt or equity to private investors. At the end of the period, a third-party evaluator determines the success of the program. If the “social outcomes” are achieved, the government repays the investors the principal as well as a return on investment proportional to the presumed public savings. If the outcomes are not achieved, the investors are not repaid.2

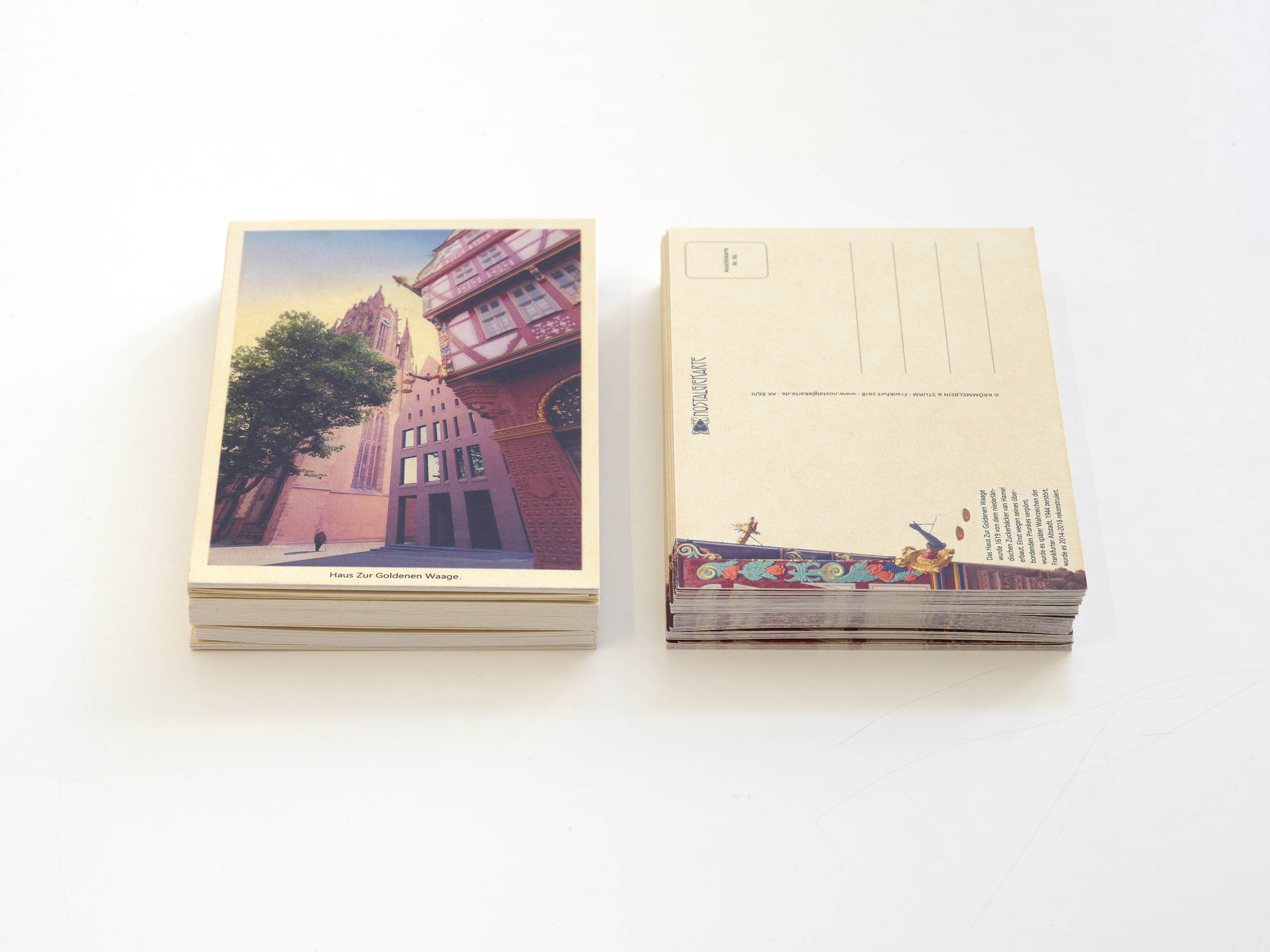

Social Impact Bonds reorient the focus of social services as they “transfer the financial risk of prevention programs to private investors based on the expectation of future recoverable savings. They also provide the incentive for multiple government agencies to work together, capturing savings across agencies to fund investor repayment.”3 The first Social Impact Bond was realized in 2010 in Peterborough, UK, and was designed to reduce recidivism at HM Prison in Peterborough.4 The first Social Impact Bond in the United States was realized in New York City in 2012 and was intended to reduce recidivism of 16–18 year olds at Rikers Island Jail.5 Since 2010, numerous Social Impact Bonds have been initiated throughout the United States, the UK, and Europe to fund temporary programs to reduce dependency on the state by reducing recidivism, reducing homelessness, reducing the number of children in foster care, and increasing workforce development.6

On June 21, 2016, the U.S. House of Representatives passed The Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act, sponsored by former Republican Representative Todd Young of Indiana. The Act would provide federal support and oversight to incentivize the implementation of Social Impact Bonds as part of “Social Impact Partnership Projects.” Under the Act, a Social Impact Partnership Project “must produce one or more measurable, clearly defined outcomes that result in social benefit and Federal savings.”7

In 2011, the Supreme Court ordered the State of California to reduce prison overcrowding.8 To comply with this order without directly reducing the total number of people incarcerated, the State of California passed the 2011 Public Safety Realignment Act. Under the Realignment laws, “newly-convicted low-level offenders without current or prior serious or violent offenses stay in county jail to serve their sentence.”9 The law shifted the distribution of these would-be state prisoners to county jails, many of which had already been operating at or above capacity.10 In 2014, California passed Assembly Bill 1837 enacting the Social Innovation Financing Program to reduce recidivism at the county level by funding outcome payments for Social Impact Bonds.11

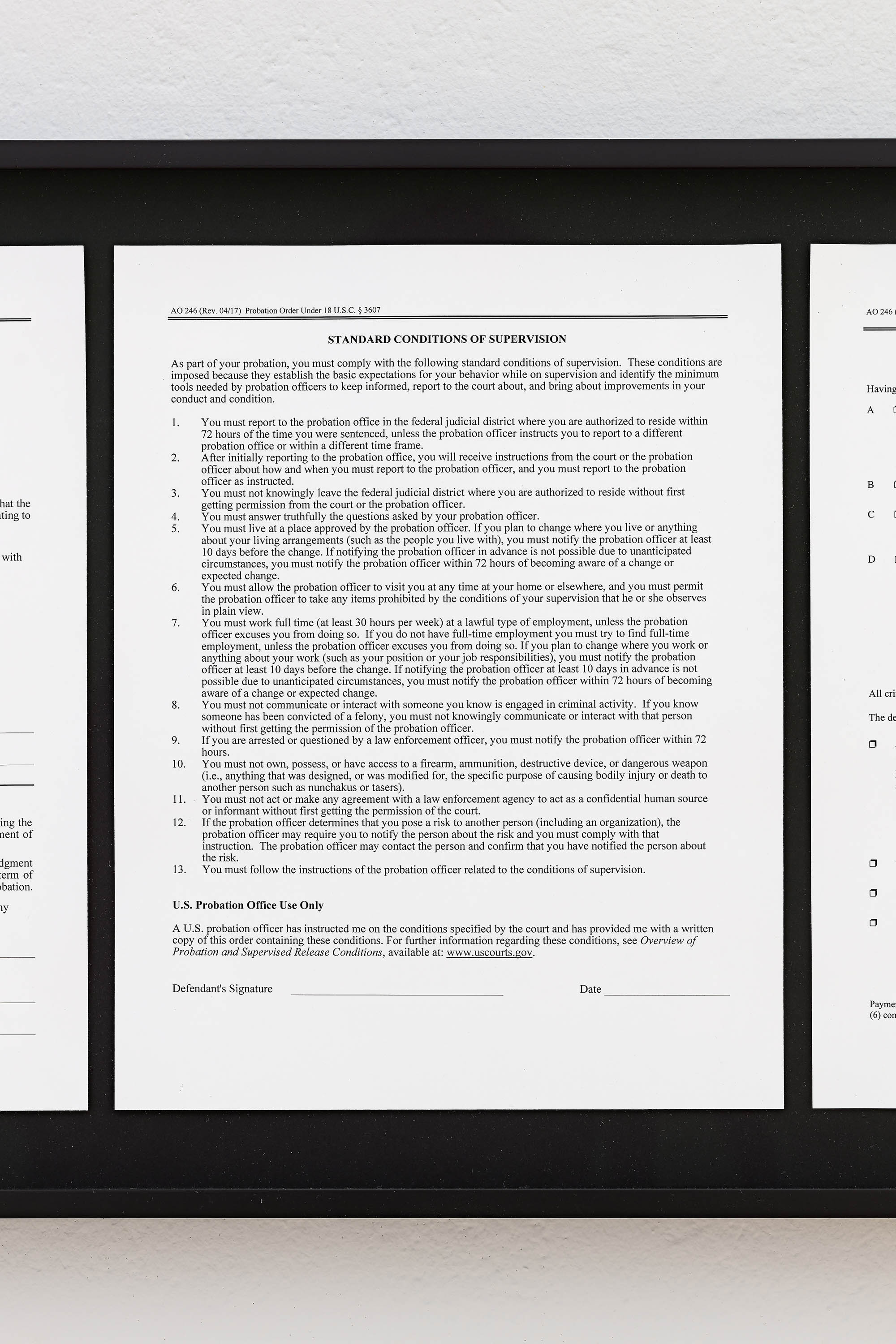

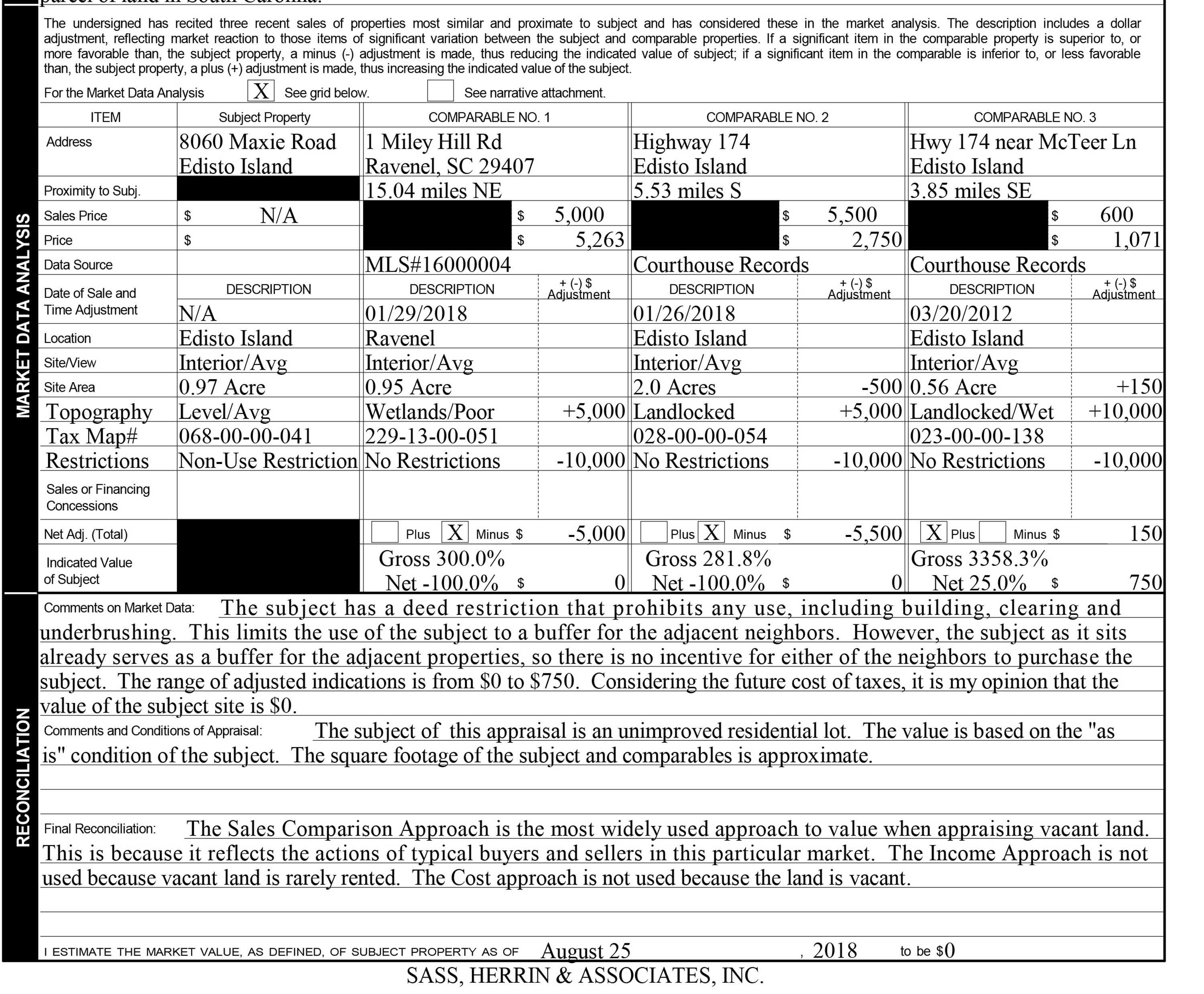

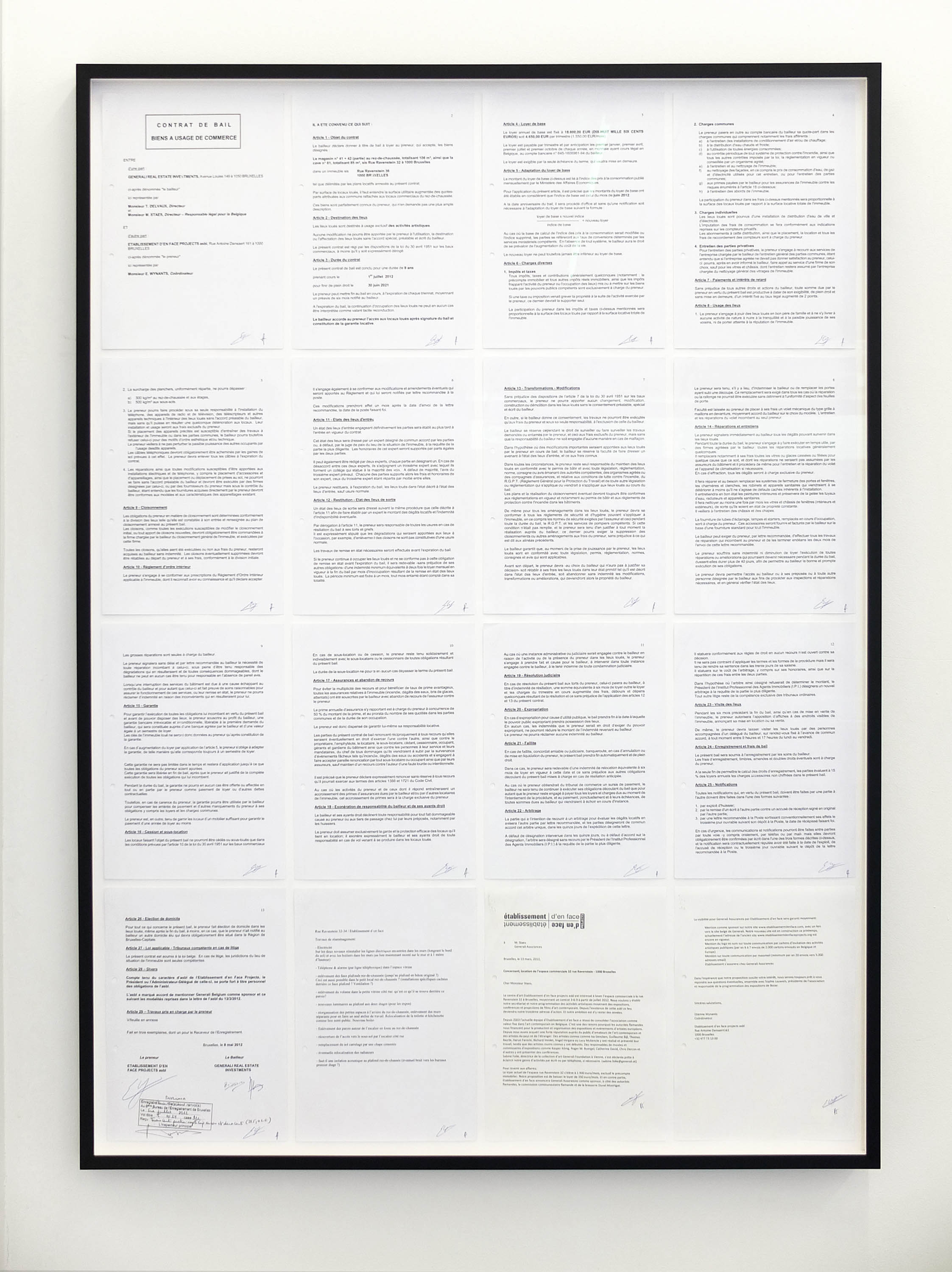

Since 2012, grand jury reports have indicated overcrowding at jails throughout Ventura County resulting from Realignment.12 In 2015, Ventura County partnered with Social Finance, Inc., as an intermediary and Interface Children and Family Services as a service provider to initiate a Social Impact Bond to reduce recidivism. The Ventura County Project to Support Reentry will focus on the use of Moral Reconation Therapy® (MRT), a “cognitive-behavioral treatment system that leads to enhanced moral reasoning, better decision making, and more appropriate behavior.”13 The founders of MRT claim it has been used in a wide range of correctional settings “[b]ecause of its remarkable success (notably with minority participants) . . . MRT research shows that participation and program completion by minority groups can significantly lower recidivism rates.”14 The Ventura County Project to Support Reentry will use MRT to treat “criminogenic thinking” defined as “antisocial attitudes, values, and beliefs.”15 The Ventura County Project to Support Reentry will make outcome payments to investors based on individual avoided arrests (as compared with a control group), and individual “clean quarters” or full quarters without arrest.16 The focus on recidivism to reduce overcrowding in California’s county jails emphasizes the personal responsibility of prisoners for their arrests, rather than changing policy to reduce arrests, convictions, or sentences.17

1 Investing in What Works: “Pay for Success” in New York State Increasing Employment and Improving Public Safety (Albany: New York State Division of the Budget, 2014), 1.

2 Jeffrey Liebman and Alina Sellman, Social Impact Bonds: A Guide for State and Local Governments (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School Social Impact Bond Technical Assistance Lab, 2013), 8.

3 A New Tool for Scaling Impact: How Social Impact Bonds Can Mobilize Private Capital to Advance Social Good (Boston: Social Finance, 2012), 5.

4 Emma Disley and Jennifer Rubin, Phase 2 Report from the Payment by Results Social Impact Bond Pilot at HMP Peterborough (London, UK: Ministry of Justice, 2014), 1.

5 The NYC ABLE Project for Incarcerated Youth: America’s First Social Impact Bond (New York: City of New York Office of the Mayor, 2012), 1.

6 “Social Impact Bonds and Development Impact Bonds Worldwide,” Instiglio, accessed November 10, 2016. http://www.instiglio.org/en/sibsworldwide/.

7 Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act, H.R. 5170, 114th Cong. § 2(c)(2)(B) (2016).

8 In 2001, the class action lawsuit Plata v. Brown was filed on the basis of inadequate state prison medical services in California that violated the cruel and unusual punishment clause of the Eighth Amendment, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. First Amended Complaint Class Action at 2, Plata v. Brown, (N.D. Cal. Aug. 1, 2001) (No. C-01-1351 TEH); Brown v. Plata 563, U.S. 1, 1-3 (2011).

9 California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 2011 Public Safety Realignment, accessed February 20, 2017, http://www.cdcr.ca.gov/realignment/docs/realignment-fact-sheet.pdf.

10 Public Policy Institute of California, Evaluating the Effects of California’s Corrections Realignment on Public Safety, August 2012, accessed February 20, 2017, http://www.ppic.org/content/pubs/report/R_812MLR.pdf.

11 A.B. 1837, 2013-2014 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Cal. 2014).

12 Ventura County Grand Jury, 2012-2013 Detention Facilities Inspections, accessed February 20, 2017, http://vcportal.ventura.org/GDJ/docs/reports/2012-13/Jail_Inspection-Final.pdf; Ventura County Grand Jury, 2013-2014 Detention Facilities Inspections, accessed February 20, 2017, http://vcportal.ventura.org/GDJ/docs/reports/2013-14/Detention_Facilities_Inspections-06.16.14.pdf; Ventura County Grand Jury, 2014-2015 Detention Facilities Inspections, accessed February 20, 2017, http://vcportal.ventura.org/GDJ/docs/reports/2014-15/Detention_Facilities-06.01.15.pdf; Ventura County Grand Jury, 2015-2016 Detention Facilities Inspections, accessed February 20, 2017, http://vcportal.ventura.org/GDJ/docs/reports/201516/Annual_Detention_Facilities_and_Law_Enforcement_Issues-05.24.16.pdf.

13 “About MRT,” Moral Reconation Therapy, accessed February 20, 2017, http://www.moral-reconation-therapy.com/aboutmrt.html.

14 Ibid.

15 Ventura County Project to Support Reentry PFS Main Agreement (Boston: Social Finance, 2017), 51.

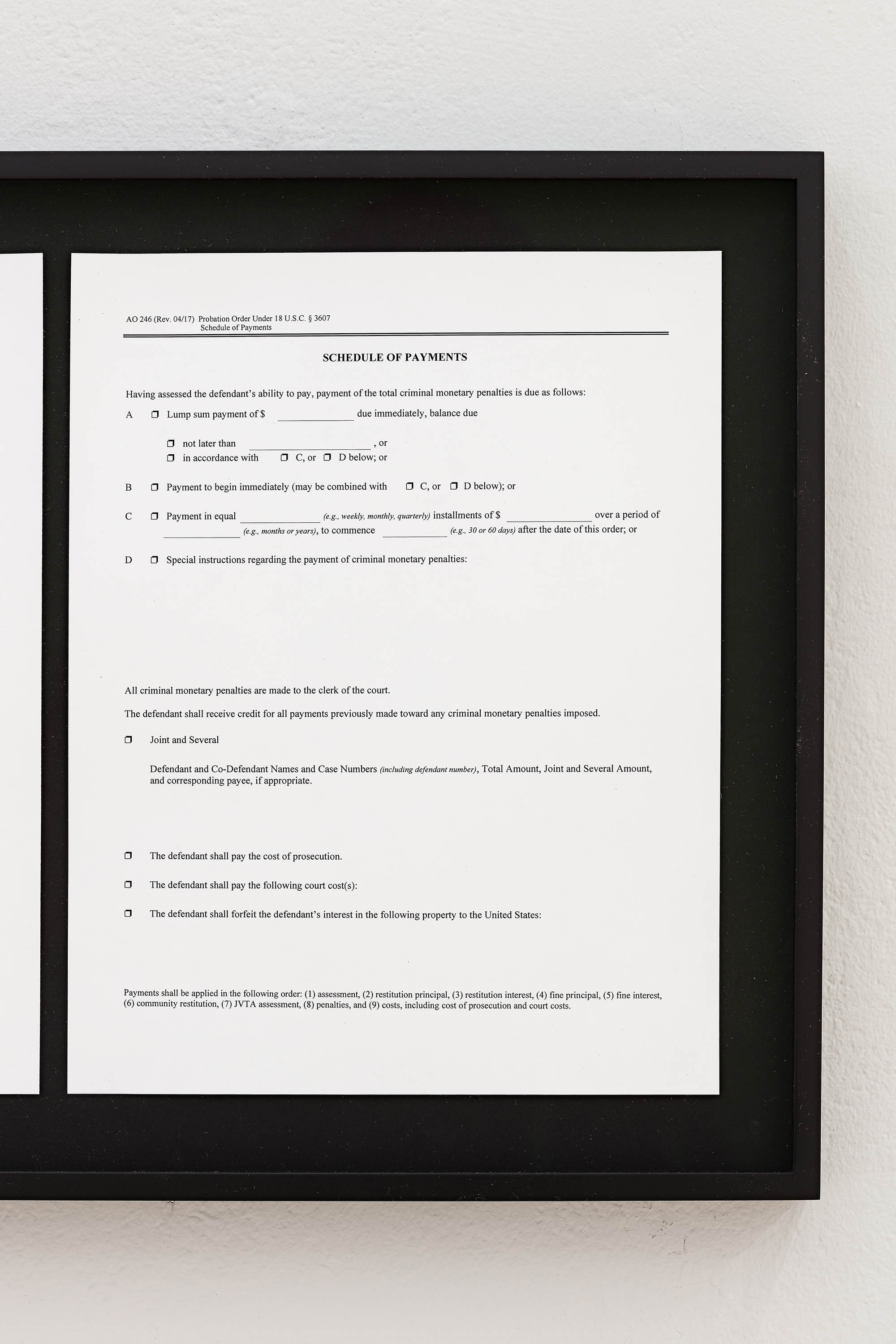

16 Avoided arrests for each cohort repay a value of “$32,000 per avoided Arrest, up to a 5% relative reduction in the Total Re-arrest Outcome between the Service Group and the Control Group. $4,500 per avoided Arrest, above a 5% relative reduction in the Total Re-arrest Outcome between the Service Group and the Control Group.” Clean quarters repay a value of “$640 for each Individual Clean Quarters Outcome. The aggregate Total Clean Quarters Outcome Payments for all Enrolled Service Group Members will be capped at $750,000.” Ventura County Project to Support Reentry PFS Main Agreement (Boston: Social Finance, 2017), 112.

17 Since 2009, the State of California has convicted less than 70% of all Adult Felony Arrests. California Department of Justice, Crime in California 2015, accessed February 20, 2017, https://oag.ca.gov/sites/all/files/agweb/pdfs/cjsc/publications/candd/cd15/cd15.pdf.