Cameron Rowland

Deputies

May 1 - June 19, 2021

— Pamphlet

— Life and Property

— Art Agenda

— Artforum

— New York Times

— Art in America

All Images

Close

Cameron Rowland

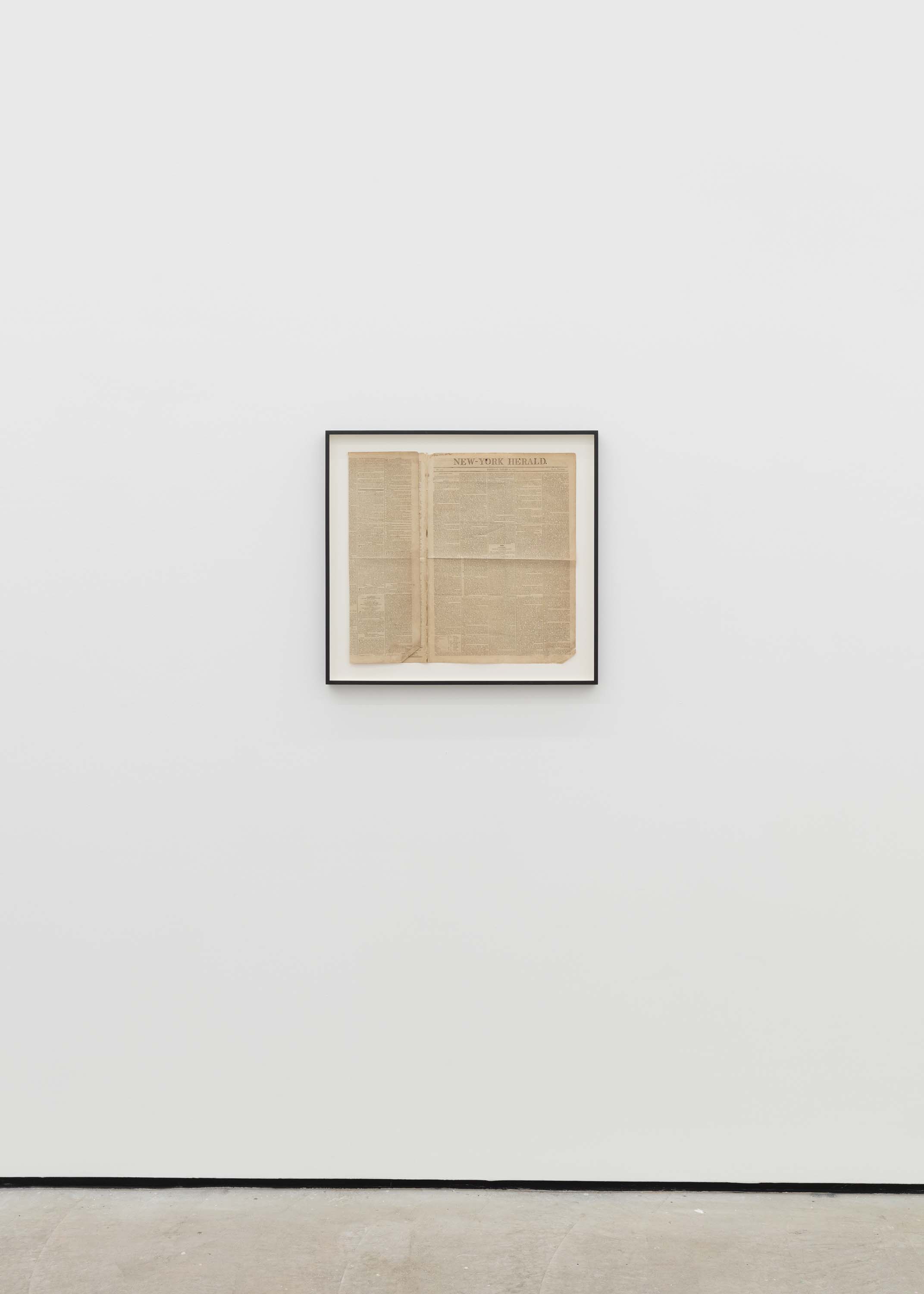

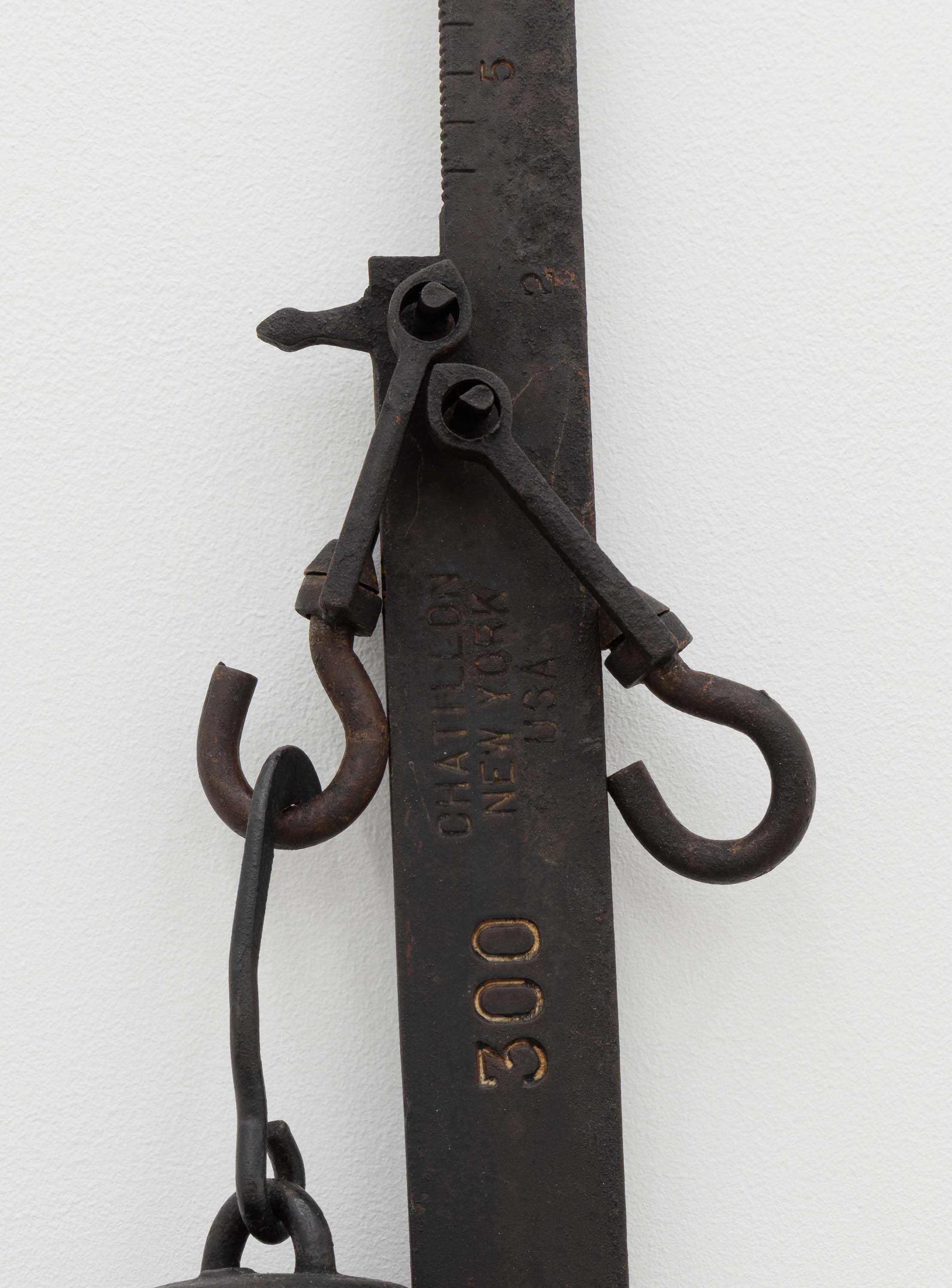

Description, 2021

New York Herald, January 26, 1803

Matching a description in the vicinity of a reported crime is often considered sufficient to meet the standard for reasonable suspicion.

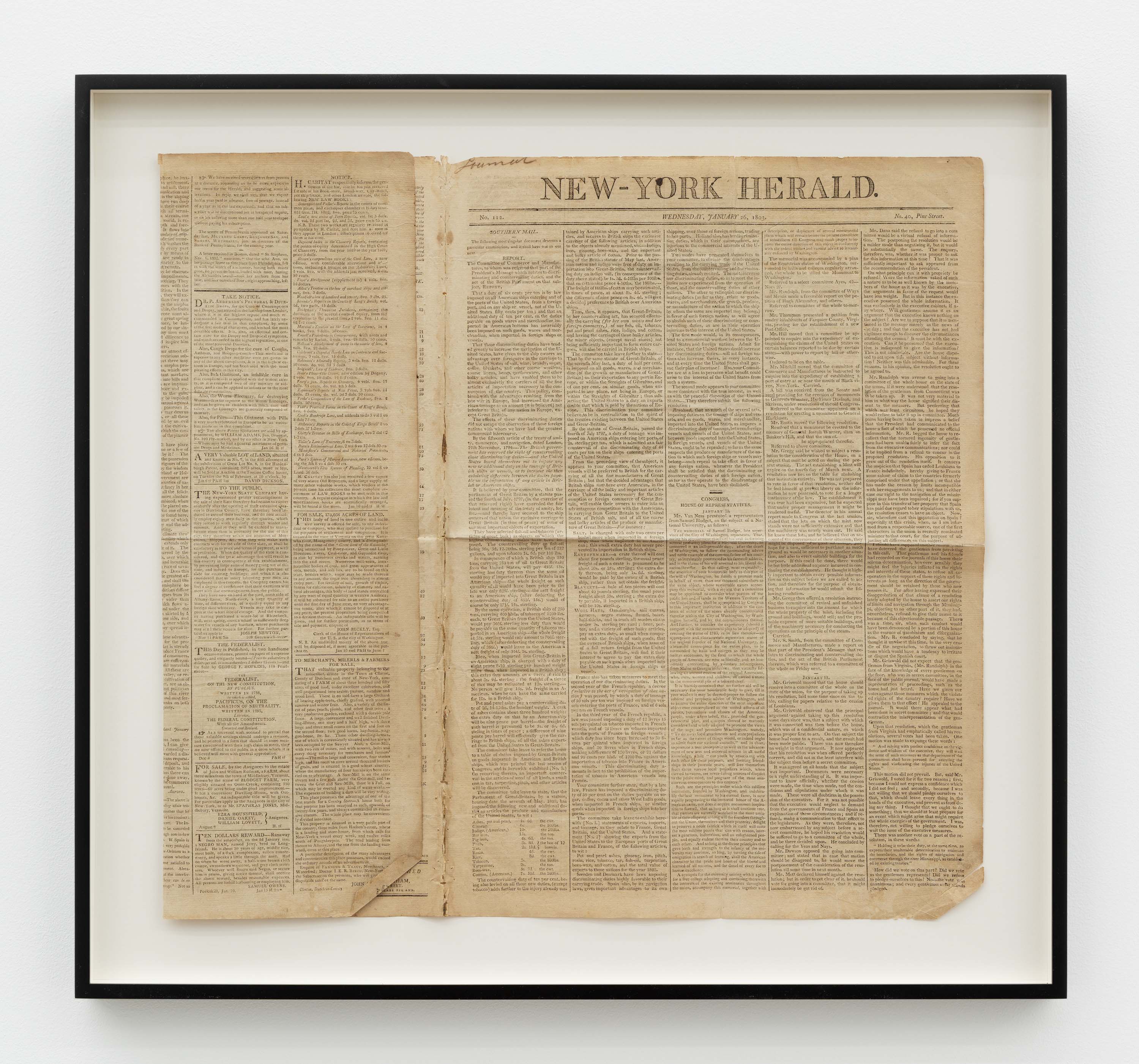

Cameron Rowland

Description, 2021

New York Herald, January 26, 1803

Detail

Cameron Rowland

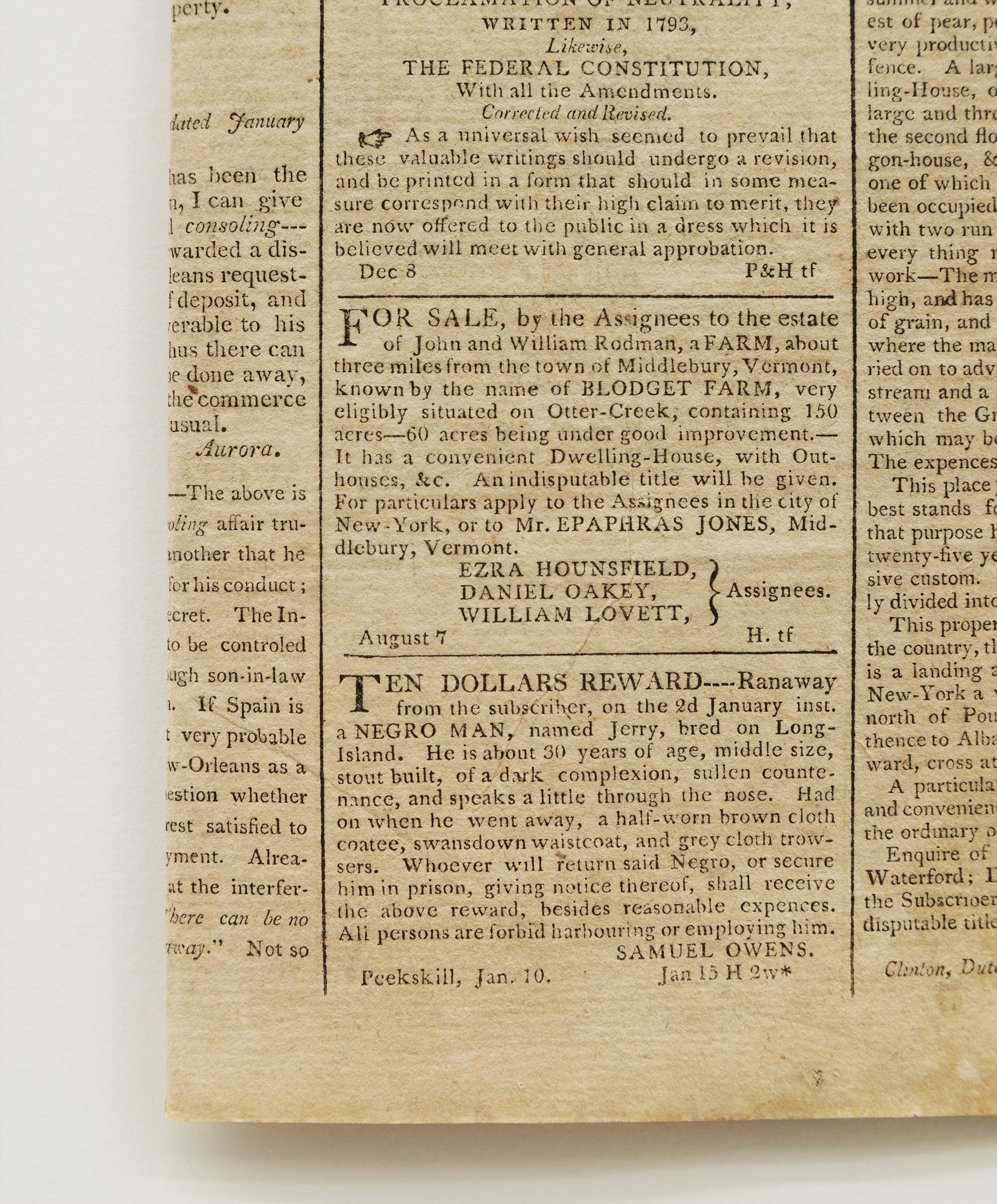

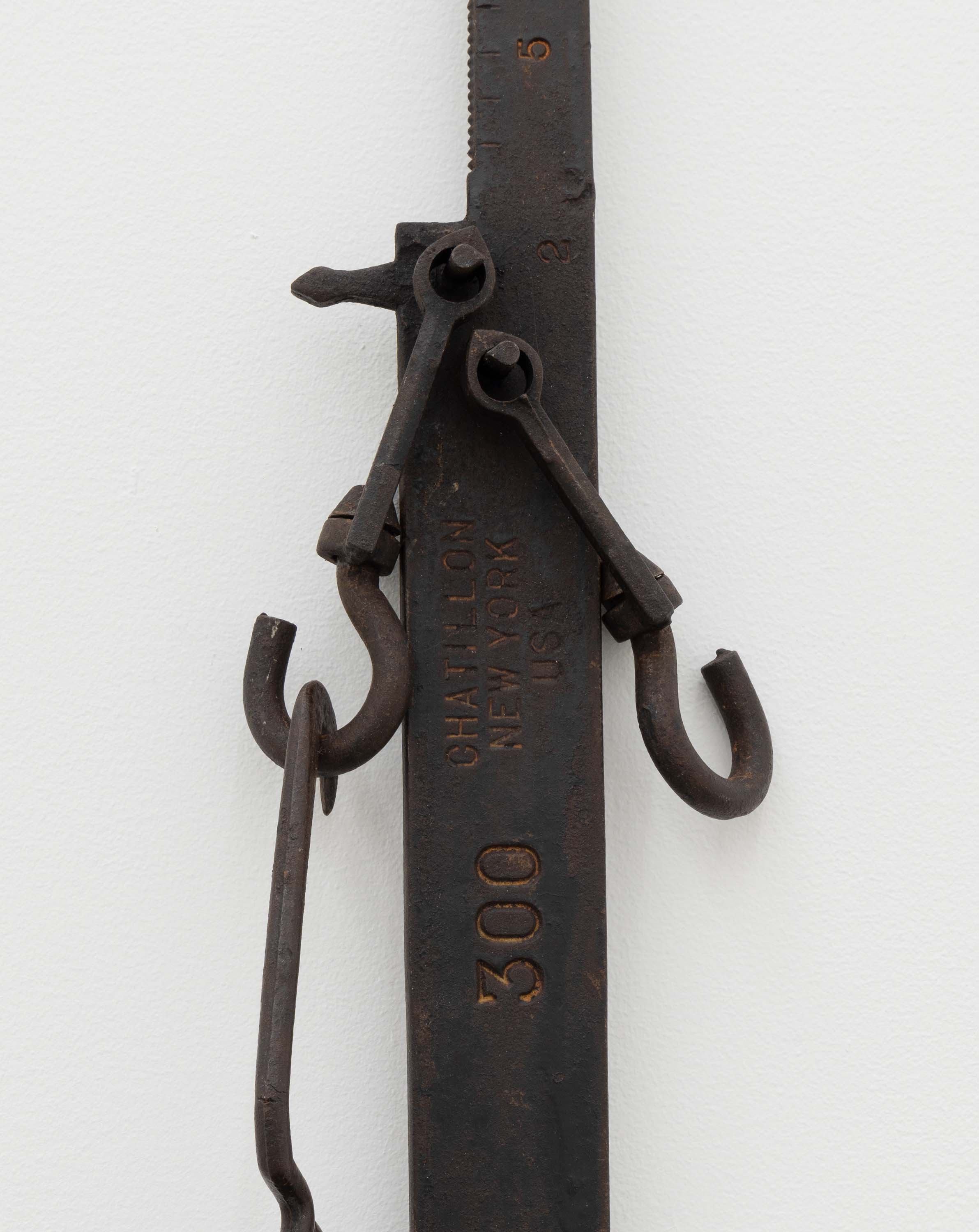

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Rental

Raw cotton is measured by weight. Between 1800 and 1865 the standard cotton bale size ranged between 300and 400 pounds. Cotton scales were not only used on the plantation for the daily weigh up, but were also used by merchants at every major port to ensure the consistency of each bale. Raw cotton produced by enslaved people was typically consolidated in southeastern ports, shipped to the North, and inspected, resold, and repacked on transatlantic ships. In the early 19th century, New York became the primary shipping hub in the nation.

New York merchants such as the Brown Brothers, the Lehman Brothers, Stephen Whitney, John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Archibald Gracie were dependent on the Southern plantation system. A committee appointed by the Alabama legislature in the early 1830s estimated that a third of the price of cotton was retained by New York merchants. In the 1850s, another group of Southerners estimated that this share had grown to 40%. Brown Brothers & Co., which now operates as the private investment firm Brown Brothers Harriman, was paradigmatic of New York firms that monopolized the trade and shipment of cotton, as well as plantation lending. Southern plantations depended on lines of credit provided by merchant firms. These lines of credit kept plantation owners in debt to their Northern merchants, giving these merchants control over the pricing and profits of plantation products. All profits of the cotton trade were extracted from the life of the enslaved. The North outsourced the management of the plantation system to the master, overseer, patroller, and the emergent system of interstate policing.

Scale producer John Chatillon & Sons Company was formed in 1835 in New York City and supplied cotton scales throughout the country. Chatillon is a subsidiary of Ametek, which is publicly traded on the NYSE and is part of the S&P 500.

Cameron Rowland

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Rental

Cameron Rowland

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches 40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Rental

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Raw cotton is measured by weight. Between 1800 and 1865 the standard cotton bale size ranged between 300and 400 pounds. Cotton scales were not only used on the plantation for the daily weigh up, but were also used by merchants at every major port to ensure the consistency of each bale. Raw cotton produced by enslaved people was typically consolidated in southeastern ports, shipped to the North, and inspected, resold, and repacked on transatlantic ships. In the early 19th century, New York became the primary shipping hub in the nation.

New York merchants such as the Brown Brothers, the Lehman Brothers, Stephen Whitney, John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and Archibald Gracie were dependent on the Southern plantation system. A committee appointed by the Alabama legislature in the early 1830s estimated that a third of the price of cotton was retained by New York merchants. In the 1850s, another group of Southerners estimated that this share had grown to 40%. Brown Brothers & Co., which now operates as the private investment firm Brown Brothers Harriman, was paradigmatic of New York firms that monopolized the trade and shipment of cotton, as well as plantation lending. Southern plantations depended on lines of credit provided by merchant firms. These lines of credit kept plantation owners in debt to their Northern merchants, giving these merchants control over the pricing and profits of plantation products. All profits of the cotton trade were extracted from the life of the enslaved. The North outsourced the management of the plantation system to the master, overseer, patroller, and the emergent system of interstate policing.

Scale producer John Chatillon & Sons Company was formed in 1835 in New York City and supplied cotton scales throughout the country. Chatillon is a subsidiary of Ametek, which is publicly traded on the NYSE and is part of the S&P 500.

Cameron Rowland

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Cameron Rowland

Price per pound, 2021

300 pound New York cotton scale

40 × 5 × 7 inches (101.60 × 12.70 × 17.78 cm)

Detail

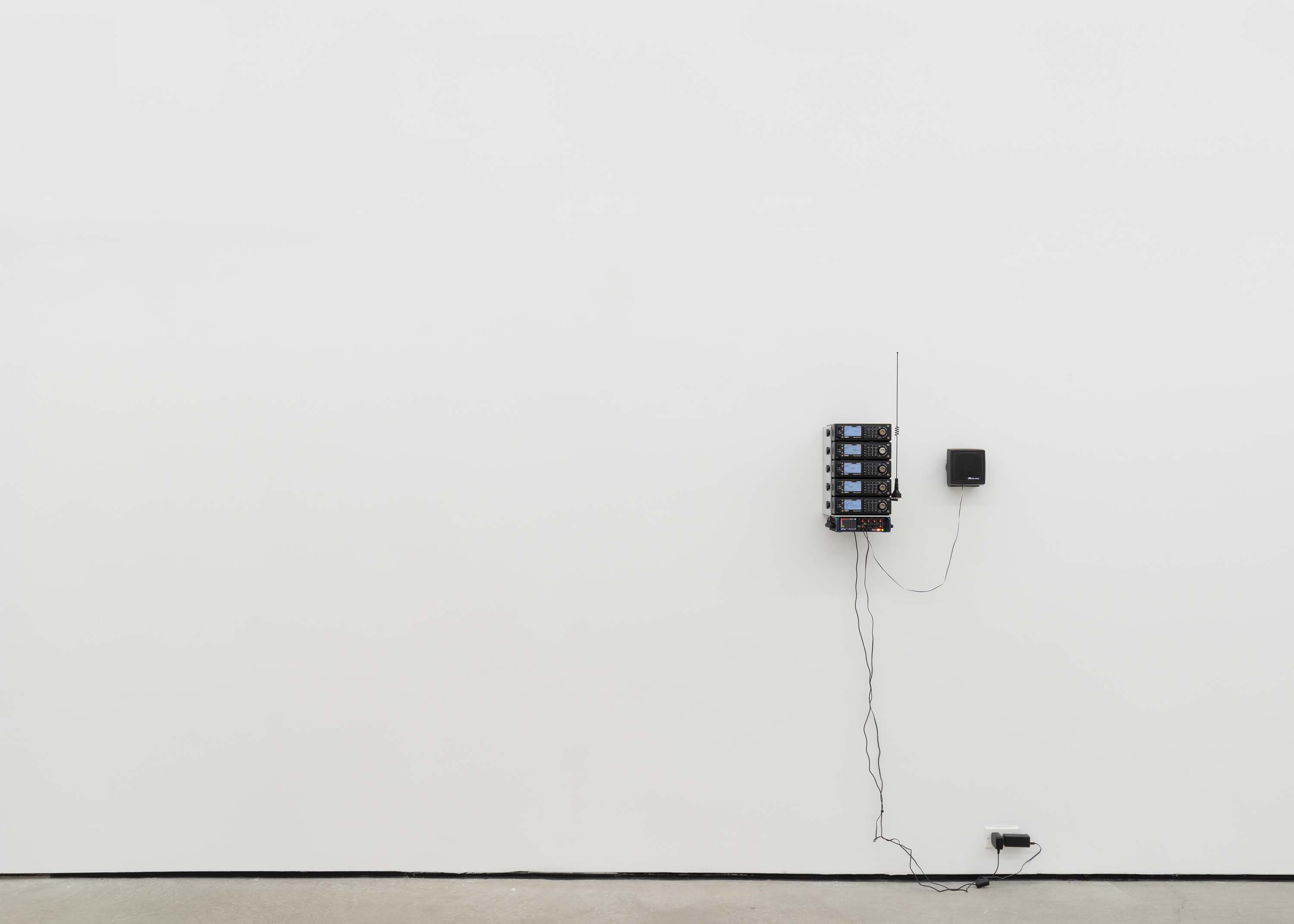

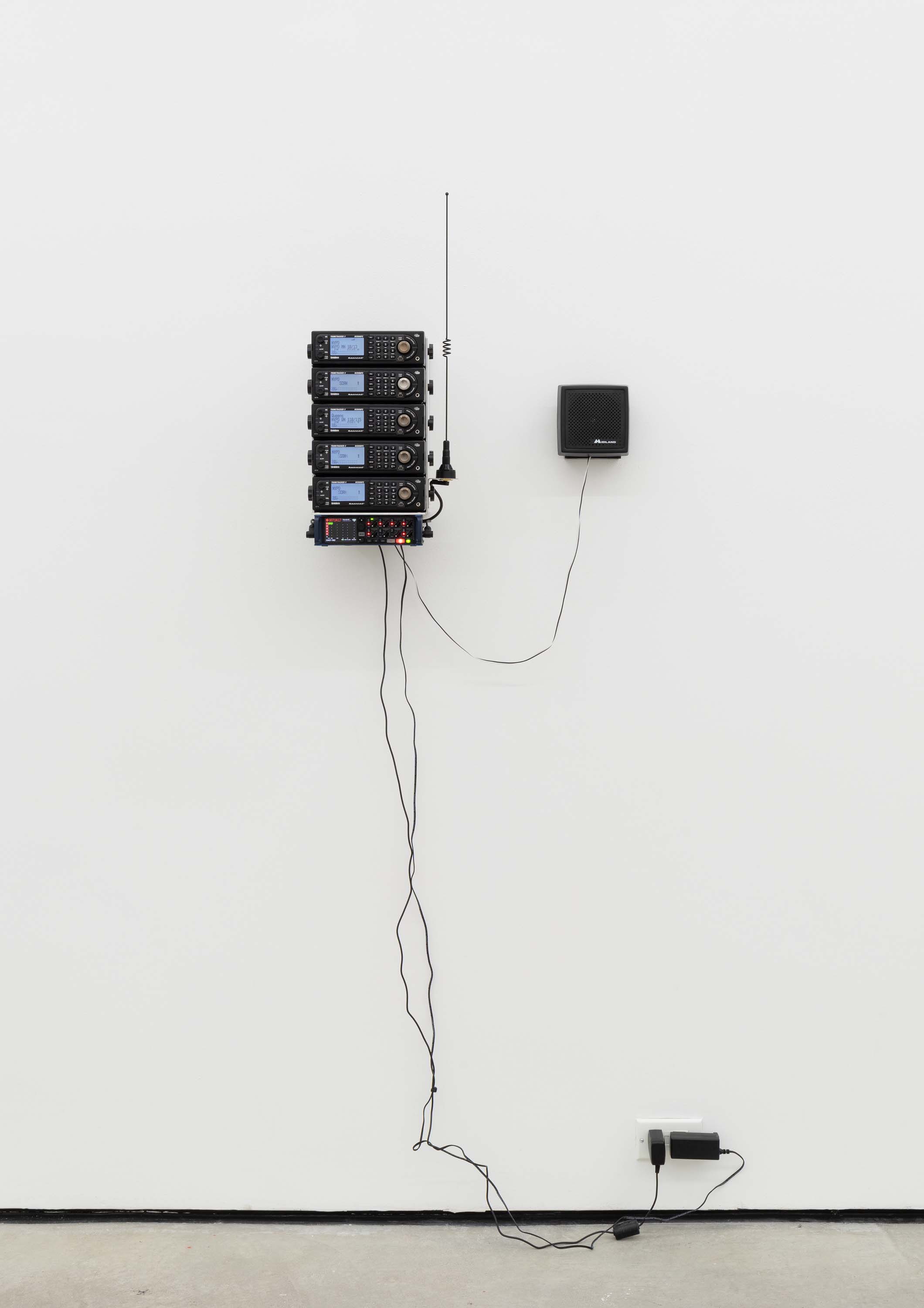

Cameron Rowland

Life and Property, 2021

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Manhattan,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Brooklyn,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in the Bronx,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Queens,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Staten Island / Citywide

The NYPD does not retain publicly accessible recordings of its two-way radio communications. These communications can be accessed live using a UHF radio scanner. Due to the amount of simultaneous radio communication throughout the city, multiple scanners are necessary to receive all transmissions. Public access to recordings of these transmissions allows these internal communications to be reviewed collectively. When Life and Property is exhibited, recordings are produced continuously. Each day the prior 24 hours of recordings are made publicly accessible on the exhibitor’s website. The recordings for each day of the exhibition are hosted as documentation.

Looking out, documenting, and inverting surveillance have always been practiced by Black targets of policing. Internal documentation of the police that is produced by the police is only available at the discretion of the police. External documentation of the police is essential to understanding what the police actually do.

The radio communications of the NYPD make evident that the vast majority of police dispatches are in response to 911calls reporting perceived disorder. The dispatches show how frequently callers report people to the police for “loitering,” “being disorderly,” “refusing to leave the business,” “panhandling,” “drinking and gambling,” “harassment,” “trespassing,” “disputing,” and “being uncooperative.”

The purpose of calling the police is to subject the accused to scrutiny, dispossession, incarceration, and death by enforcement. Calling the police to stop violence discounts the violence inflicted by the police. Survived and Punished organizes in support of incarcerated survivors of domestic and sexual violence. Their publication Research across the Walls details that:

In 2000, a study of domestic-violence survivors under New York State’s mandatory arrest policies found that survivors of domestic violence were arrested in 27 percent of cases reported through a domestic violence hotline…[A] decade-long study found that a law enforcement officer is charged with sexual misconduct every5 days, and that motorists, crime victims and witnesses and young people are the most frequent targets.

As a paramilitary institution, the primary object of the police is the protection of white citizens and the property they own. White citizenship remains the benchmark for legal protection the United States. 42 USC § 1981, “Equal rights under the law,” last updated in 1991, states that:

(a) Statement of equal rights. All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

The designation of who the police are sworn to protect is determined by the de jure and de facto withholding of citizenship. The NYPD’s mission statement openly states that its protection is contingent on citizenship as it pledges to:

Protect the lives and property of our fellow citizens and impartially enforce the law.

Cameron Rowland

Life and Property, 2021

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Manhattan,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Brooklyn,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in the Bronx,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Queens,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Staten Island / Citywide

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Life and Property, 2021

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Manhattan,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Brooklyn,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in the Bronx,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Queens,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Staten Island / Citywide

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Life and Property, 2021

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Manhattan,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Brooklyn,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in the Bronx,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Queens,

Recording of NYPD radio communications in Staten Island / Citywide

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Lynch Law in America, 2021

Emergency call tower

114 × 10 × 8 inches (289.56 × 25.40 × 20.32 cm)

[Lynching] is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an “unwritten law” that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal.

—Ida B. Wells, “Lynch Law in America,” 1900

Emergency calls to the police are built on lynch law. Calling the police is a request that someone be injured, arrested, incarcerated, or killed. Calling the police is participation in an authority that uses lynching as law enforcement. Descriptions given to the police provide the grounds for stops of anyone who matches them.

The power of white people to enforce the law and invoke legal authority was the basis for colonial slave codes. The1740 Slave Codes in South Carolina determined that if enslaved people did not submit to searches by white colonists, they could be lawfully killed. If any slave, found out of the house or plantation to which they were bound, “shall refuse to submit or undergo the examination of any white person, it shall be lawful for any such white person to pursue, apprehend, and moderately correct such slave; and if any such slave shall assault and strike such white person, such slave may be lawfully killed.”

The racist legal practice of matching a description has been practiced in the United States since its founding. Article IV, Section 2, Clause 3 of the Constitution is known as the Fugitive Slave Clause. It dictates that any slave who absconds to a state that has abolished slavery does not become free, but legally remains the property of the master. The regular fugitivity of the enslaved caused the framers of the Constitution to prioritize the recognition, recapture, and return of enslaved property. The Fugitive Slave Clause was enhanced by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which stipulated that:

it shall be the duty of the executive authority of the State or Territory to which such person shall have fled, to cause him or her arrest to be given to the Executive authority making such demand, or to the agent when he shall appear….[A]nd upon proof to the satisfaction of such judge or magistrate, either by oral testimony or affidavit taken before and certified by a magistrate of any such state or territory, that the person so seized or arrested, doth, under the laws of the state or territory from which he or she fled, owe service or labour to the person claiming him or her, it shall be the duty of such judge or magistrate to give a certificate thereof to such claimant, his agent or attorney, which shall be sufficient warrant for removing the said fugitive from labour, to the state or territory from which he or she fled.

Enforcement of the fugitive slave laws allowed any Black person matching a description to be accused of being a fugitive, and to be drawn into or returned to slavery.

In the absence of formal slavery, the sharecropping system, the lynch mob, the Ku Klux Klan, and the professional police collaboratively formed a regime of racial terror intended to control the labor and life of Black people across the country. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, police facilitated and participated in lynch mobs. Police continue the practice of lynching as enforcement of the “unwritten law.”

Cameron Rowland

Lynch Law in America, 2021

Emergency call tower

114 × 10 × 8 inches (289.56 × 25.40 × 20.32 cm)

Cameron Rowland

Lynch Law in America, 2021

Emergency call tower

114 × 10 × 8 inches (289.56 × 25.40 × 20.32 cm)

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Lynch Law in America, 2021

Emergency call tower

114 × 10 × 8 inches (289.56 × 25.40 × 20.32 cm)

Detail

Cameron Rowland

Church Avenue and Bedford Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

Van Cortlandt Park, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

90th Street and Corona Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

126th Street and 2nd Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

212th Street and 10th Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

The dread of “an uprising of blacks” in 1722 prompted an act providing that all negroes and blacks be buried by daylight. The act was amended afterward so that not more than twelve negroes should attend a funeral. The penalty for the violation of this statute was a public flogging. Furthermore, the slave was to be buried without any outward signs of grief or any ceremonial tokens, such as a pall, gloves or flowers.

—New York Times, April 12, 1903

In 1991, the Government Services Administration began construction on the Ted Weiss Federal Building in New York City. During construction human remains were disinterred. Historical analysis identified the site as a Black burial ground. Black protests against the GSA’s treatment of the site led to a large-scale archeological survey. The building was still built. Part of the site was reserved for The African Burial Ground Monument on Duane Street. By naming it “The African Burial Ground Monument,” the site is portrayed as the only Black burial ground in the city.

There are numerous unmarked Black burial grounds throughout New York City.

At Church Avenue and Bedford Avenue in Brooklyn there is a 17th–19th century unmarked Black burial ground.

At Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx there is a 17th–19th century unmarked Black burial ground.

At 90th Street and Corona Avenue in Queens there is a 19th–20th century unmarked Black burial ground.

At 126th Street and 2nd Avenue in Manhattan there is a 17th–19th century unmarked Black burial ground.

At 212th Street and 10th Avenue in Manhattan there is a 17th–19th century unmarked Black burial ground.

Many of these burial grounds did not have individual plots, but were made as collective graves. Many of those buried did not own the property of their resting place. Some of these burial grounds have been built over with bus terminals, schools, car mechanics, and homes. They remain unmarked. The Black burial ground has traditionally been a site of plotting and rebellion. Their unmarked status has served this purpose.

Despite identifying as an abolitionist, William H. Seward, U.S. Secretary of State from 1861–1869, favored compensating slave owners for their loss of enslaved property and designed President Andrew Johnson’s Declaration of Amnesty in 1865, reinstating former Confederates’ property. Seward co-wrote Johnson’s 1866 veto of the Freedmen’s Bill that would have extended the existence of the Freedmen’s Bureau. He also co-wrote Johnson’s veto of the 15th Amendment, in an attempt to continue the disenfranchisement of Black people. Seward’s vision of reunification allowed for emancipation, but foreclosed the recognition of Black people as human.

Five unauthorized benches have been put in Seward Park. These benches are the same 19th century design that is used throughout the park. These benches are titled after the locations of five unmarked Black burial grounds throughout the city. The displaced acknowledgements of these burial grounds intervene on Seward’s memorial. They are meant for resting or remembering or plotting.

Cameron Rowland

Church Avenue and Bedford Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

Cameron Rowland

Van Cortlandt Park, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

Cameron Rowland

90th Street and Corona Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

Cameron Rowland

126th Street and 2nd Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park

Cameron Rowland

212th Street and 10th Avenue, 2021

Bench in Seward Park