Cameron Rowland

Properties

Solo Exhibition

Dia Art Foundation, Beacon, New York

October 4, 2024 – October 20, 2025

— Pamphlet

— Link

— Talks

— e-flux

— Flash Art

— Art Review

— Cultured

— Artforum

— Artforum

— 4Columns

— Glasstire

— The Brooklyn Rail

All Images

Close

Cameron Rowland

Properties, Dia Art Foundation, Beacon, New York, 2024

Installation view

Cameron Rowland

Properties, Dia Art Foundation, Beacon, New York, 2024

Installation view

Cameron Rowland

Properties, Dia Art Foundation, Beacon, New York, 2024

Installation view

Cameron Rowland

Commissary, 2024

Scythes

59.5 x 52 x 16 inches

Rental

Sharecropping was debt peonage. It was instituted to replace slave labor. It operated in explicit violation of the Thirteenth Amendment’s stated ban on involuntary servitude. Sharecropping contracts were designed to keep black people bound to the land, which their labor made valuable. Violations of the contract included leaving the plantation without permission; being loud, disorderly, drunk, or disobedient; having an “offensive weapon”; and misusing the tools. Violations were grounds for dismissal, eviction, and forfeiture of the share. In addition to cultivating the land, these contracts could include obligations to do the washing “and all other necessary house work” for the landlord’s family. Sharecroppers were forced to buy food, clothes, tools, and other necessities on credit from the landlord’s general store, also called the commissary. The commissary charged up to 70 percent interest. Debts were deducted from the cropper’s share. The contract and the commissary kept sharecroppers in perpetual debt.

W. E. B. Du Bois describes the terms of this labor as “a wage approximating as nearly as possible slavery conditions, in order to restore capital lost in the war.” Many sharecroppers were former slaves. Many sharecroppers were the children of former slaves. Slaves used scythes as tools of rebellion in Henrico County, Virginia, in 1800; in Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831; and in Coffeeville, Mississippi, in 1858. In violation of their contracts, croppers armed themselves as well. The tools of perpetual debt were also the tools of black riot.

Cameron Rowland

Increase, 2024

Bed frame

46 x 42 x 78 inches

Under slave law, partus sequitur ventrem stipulated that the “child follows the belly.” When slave owners bought black women, they also purchased the rights to what owners termed “all her future increase.”

Saidiya Hartman describes the centrality of this principle to the system of racial slavery: “The work of sex and procreation was the chief motor for reproducing the material, social, and symbolic relations of slavery. The value accrued through reproductive labor was brutally apparent to the enslaved who protested bitterly against being bred like cattle and oxen.”

This status was constructed to last forever. What Jennifer Morgan names as “the value of a reproducing labor force” has ordered the continuity of this sexual violence. Domestic work has been a principal vector for its preservation. Live-in workers have been made perpetually available to their employers.

Refusals of this availability are criminalized. Christina Sharpe makes clear that “living in/the wake of slavery is living ‘the afterlife of property’ and living the afterlife of partus sequitur ventrem (that which is brought forth follows the womb), in which the Black child inherits the non/status, the non/being of the mother. That inheritance of a non/status is everywhere apparent now in the ongoing criminalization of Black women and children.”

Non/being constitutes a position whose modalities of life and death are simultaneously structured by and unrecognizable to the capture of ownership. As Hartman writes, “The forms of care, intimacy, and sustenance exploited by racial capitalism, most importantly, are not reducible to or exhausted by it. These labors cannot be assimilated to the template or grid of the black worker, but instead nourish the latent text of the fugitive. They enable those ‘who were never meant to survive’ to sometimes do just that.”

This fugitivity is an inherent threat to the value of increase.

Cameron Rowland

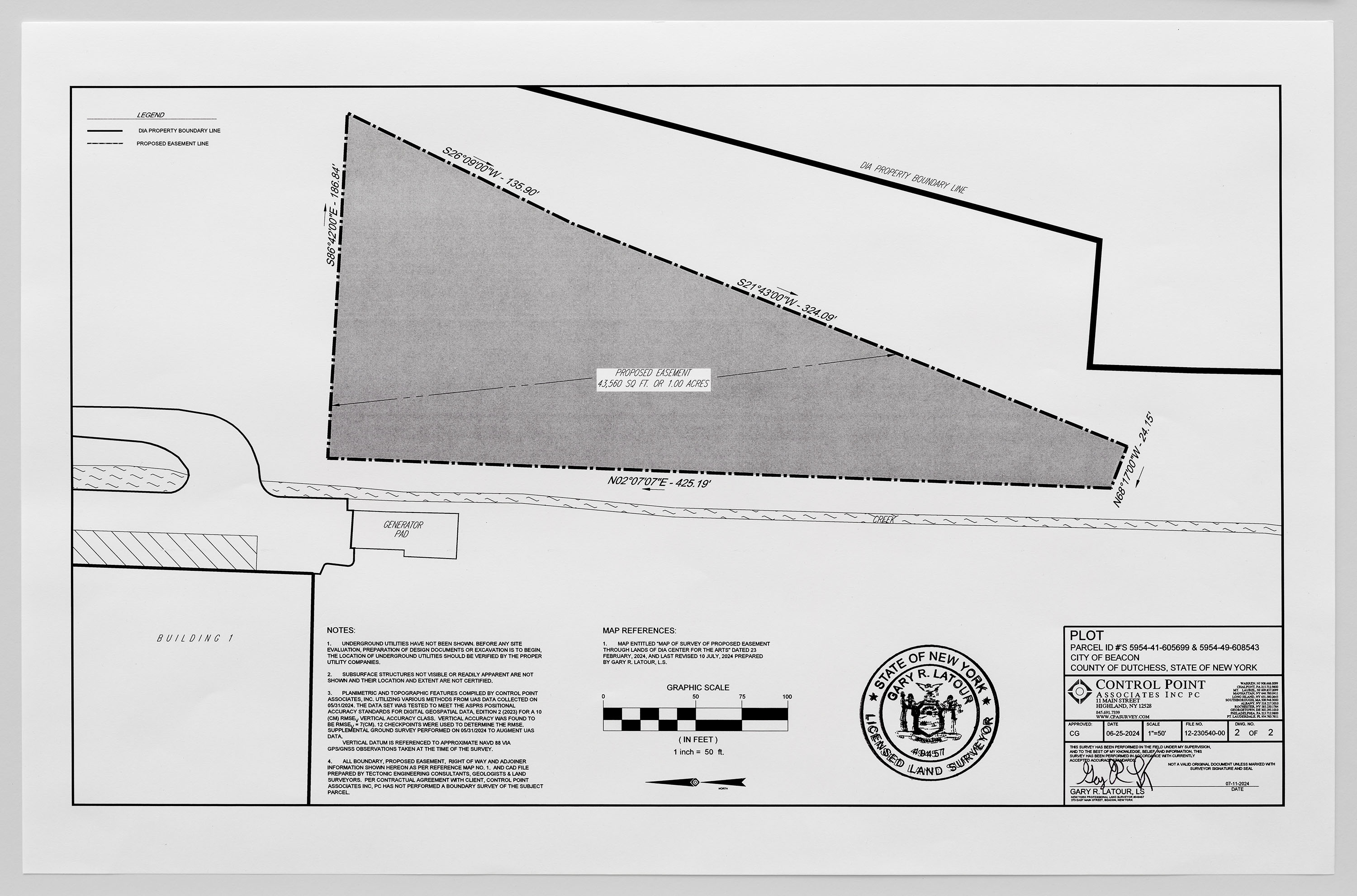

Plot, 2024

Easement, 1 acre in Beacon, New York

Black people were prohibited from being buried in cemeteries. These prohibitions were applied to both free and enslaved black people, in both the North and the South. They were meant to make the degradation of blackness permanent. Black people were buried in unmarked slave plots and unregistered black burial grounds.

For many black people these black mass graves were extensions of black life. As Sylvia Wynter describes, black mass graves were a point of connection to the “permanent future” and the “historical life of the group.” As Wynter writes of the provision grounds where slaves grew their own food, the burial plot was also “an area of experience which reinvented and therefore perpetuated an alternative world view, an alternative consciousness to that of the plantation. This world view was marginalized by the plantation but never destroyed. In relation to the plot, the slave lived in a society partly created as an adjunct to the market, partly as an end in itself.”

Black people used funerals and burial grounds to plot escape and rebellion. In response, laws banning slave funerals and grave markers were passed throughout the Caribbean and the North American colonies. As former slave John Bates said, masters who prohibited slave funerals would “jes’ bury dem like a cow or a hoss, jes’ dig de hole and roll ’em in it and cover ’em up.”

Unmarked black burials are frequently disinterred during real estate development. This has been the case for numerous burial grounds in New York State and throughout the country. Construction frequently continues despite these “discoveries.”

In 1790, the U.S. Census recorded nearly as many slaves in New York State as in Georgia. The land that Dia Art Foundation currently owns in Beacon, New York, was owned by slave owners and slave traders from 1683 until the abolition of slavery in New York in 1827.

The easement between Dia Art Foundation and Plot Inc. conveys the rights to a one-acre section of the institution’s property to Plot Inc. for the purpose of protecting the graves of enslaved people who may have been buried there. This burial ground easement runs with the land and requires Dia and all future owners to relinquish the rights to use, disturb, or develop this section of the property.

The plot will remain unmarked. It will degrade the value of the institution’s property. It challenges the assumed absence of black burials on sites of enslavement by assuming their presence.

Cameron Rowland

Underproduction, 2024 Overturned pot

18 x 21 x 16 inches

Slaves outnumbered owners on the plantation.

Slaves were an inherent risk to the plantation.

Owners banned slaves from meeting with one another. Slaves met anyway. An overturned pot placed at the door of the meeting blocked the sound of the gathering.

The overturned pot protected meetings from the slave patrol. The meetings were negations of the plantation logic of production.

Cameron Rowland

Properties, Dia Art Foundation, Beacon, New York, 2024

Installation view

Cameron Rowland

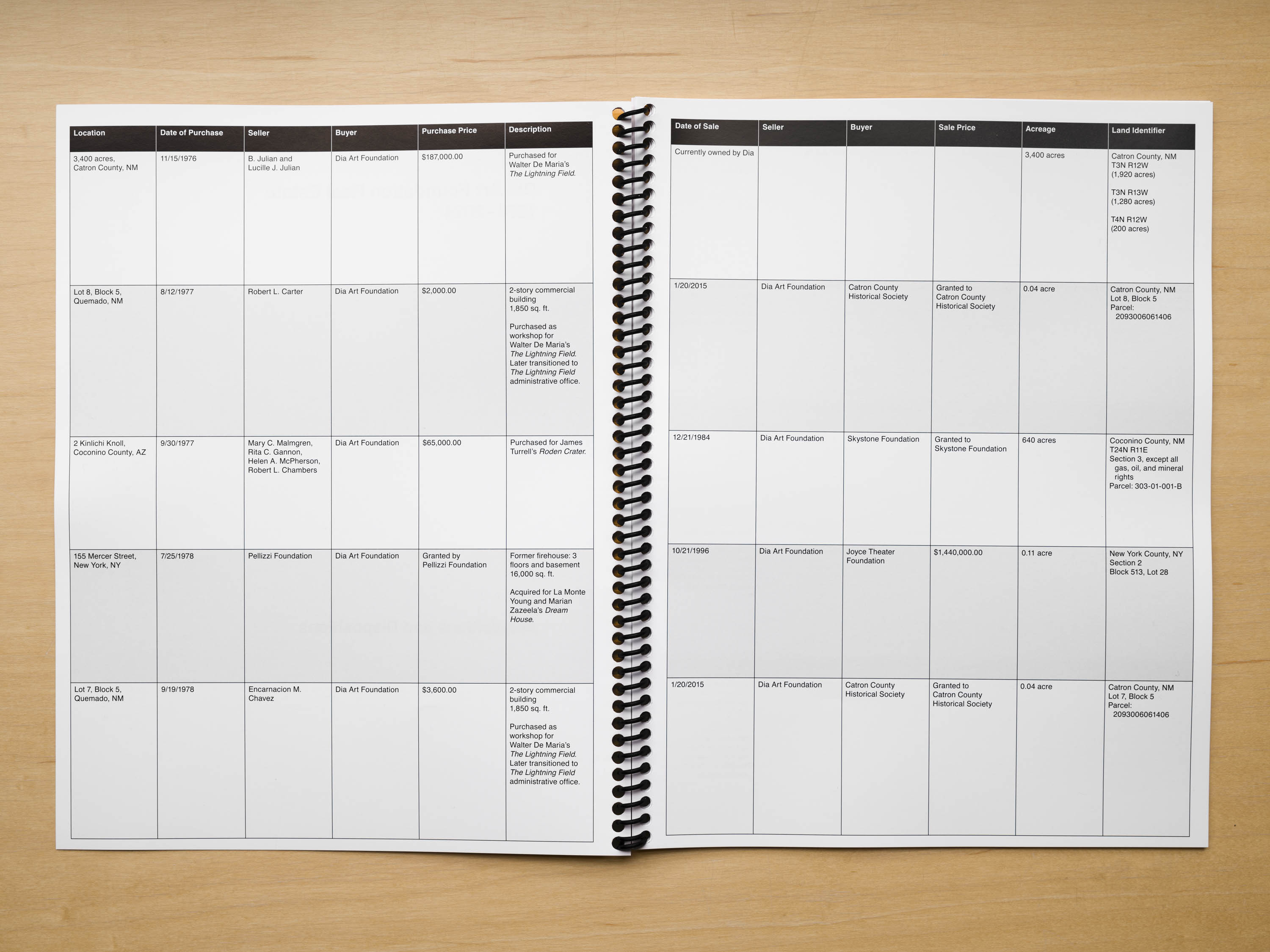

Estate, 2024

Dia Art Foundation Real Estate, 1974–2024

Books $10 each

Schlumberger Limited, established in 1926, is the largest oilfield services company in the world. Descendants of founder Conrad Schlumberger used their shares in the company to create the Dia Art Foundation. Schlumberger Limited was the primary source of funds for the first decade of the institution. During this period, Dia purchased the majority of the fifty-nine real estate properties it has owned during the past fifty years.

The properties were purchased for artists, for artworks, for offices, for exhibition spaces, and as rentals. Many of these properties were given away. Many were sold at a high rate of return. A number continue to function as rental properties, which generate over $1 million of annual income for the institution.

Dia does not retain information on the history of these properties prior to the twentieth century.

Cameron Rowland

Estate, 2024

Dia Art Foundation Real Estate, 1974–2024

Books $10 each

Schlumberger Limited, established in 1926, is the largest oilfield services company in the world. Descendants of founder Conrad Schlumberger used their shares in the company to create the Dia Art Foundation. Schlumberger Limited was the primary source of funds for the first decade of the institution. During this period, Dia purchased the majority of the fifty-nine real estate properties it has owned during the past fifty years.

The properties were purchased for artists, for artworks, for offices, for exhibition spaces, and as rentals. Many of these properties were given away. Many were sold at a high rate of return. A number continue to function as rental properties, which generate over $1 million of annual income for the institution.

Dia does not retain information on the history of these properties prior to the twentieth century.

Cameron Rowland

Estate, 2024

Dia Art Foundation Real Estate, 1974–2024

Books $10 each

Schlumberger Limited, established in 1926, is the largest oilfield services company in the world. Descendants of founder Conrad Schlumberger used their shares in the company to create the Dia Art Foundation. Schlumberger Limited was the primary source of funds for the first decade of the institution. During this period, Dia purchased the majority of the fifty-nine real estate properties it has owned during the past fifty years.

The properties were purchased for artists, for artworks, for offices, for exhibition spaces, and as rentals. Many of these properties were given away. Many were sold at a high rate of return. A number continue to function as rental properties, which generate over $1 million of annual income for the institution.

Dia does not retain information on the history of these properties prior to the twentieth century.

Cameron Rowland

Night Mail, 2024

Distribution of 1000 exhibition pamphlets by hand

Black communists distributed their pamphlets by hand, circumventing the scrutiny of the postal system. They distributed them to sharecroppers, employees, managers, and landlords. Under seditious-communication laws these publications were illegal. Police called these pamphlets “night mail.”