Hamishi Farah

Black Painting

September 6 - October 21, 2023

— Text by Hannah Black

— New York Times

All Images

Close

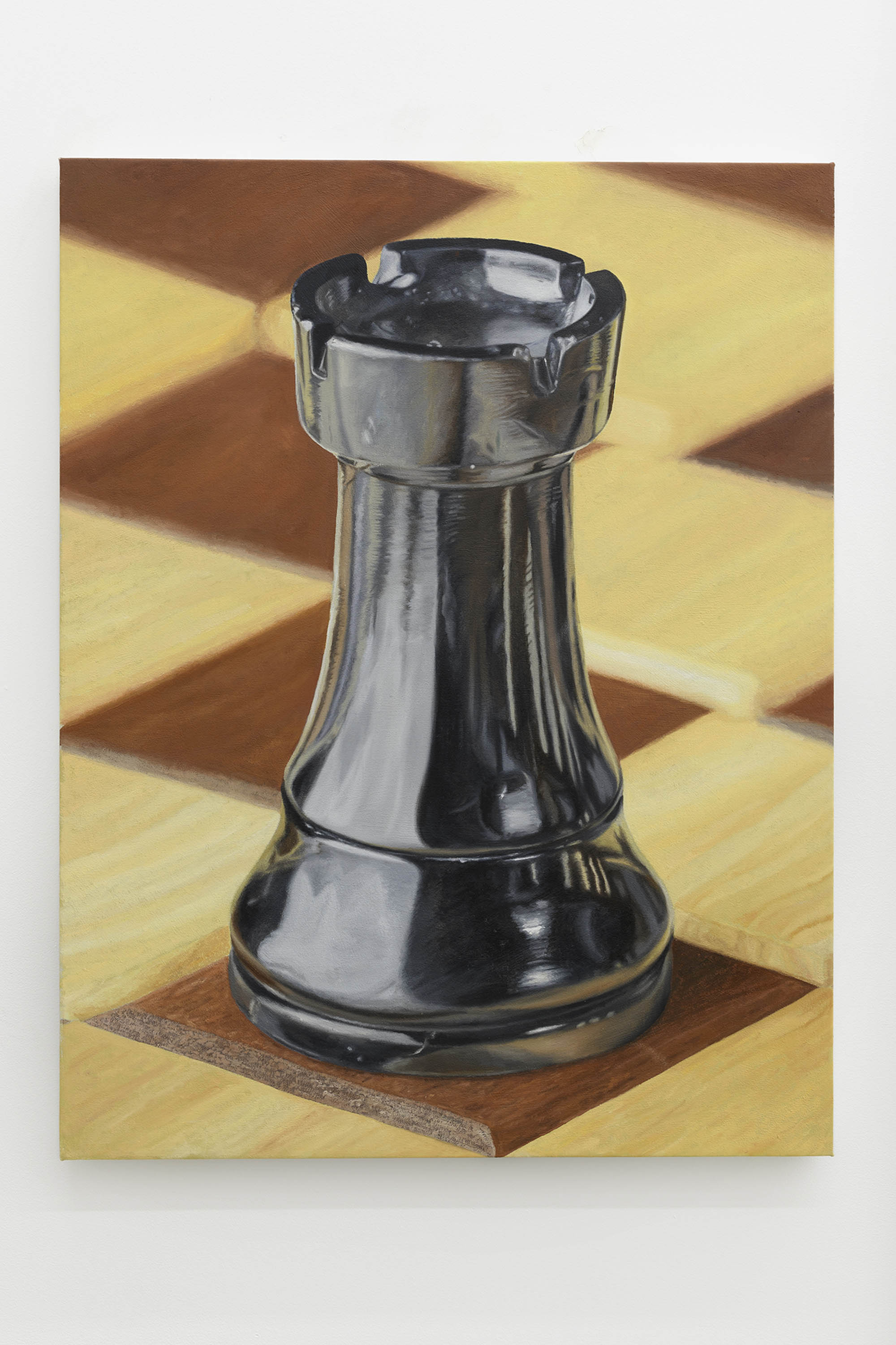

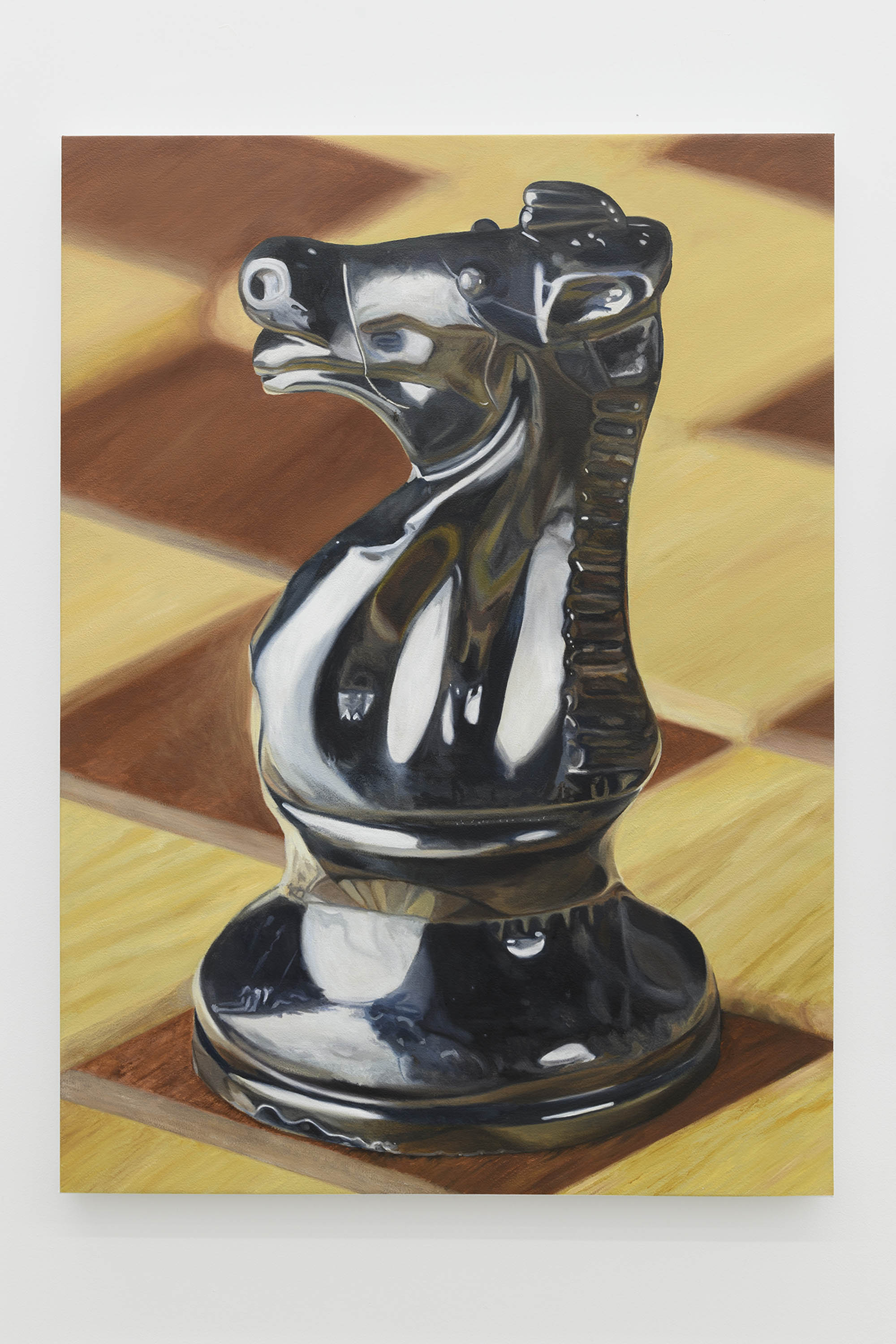

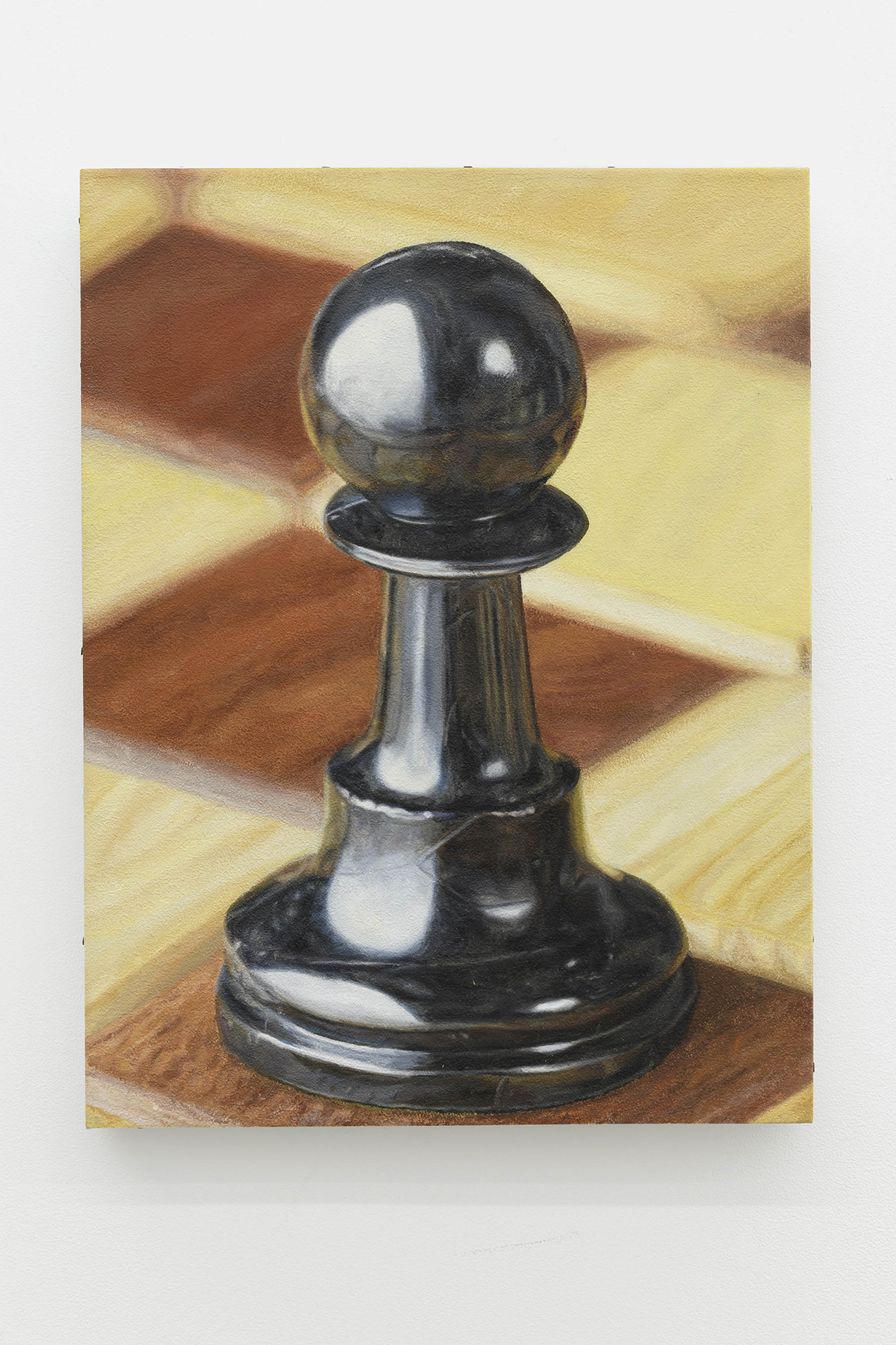

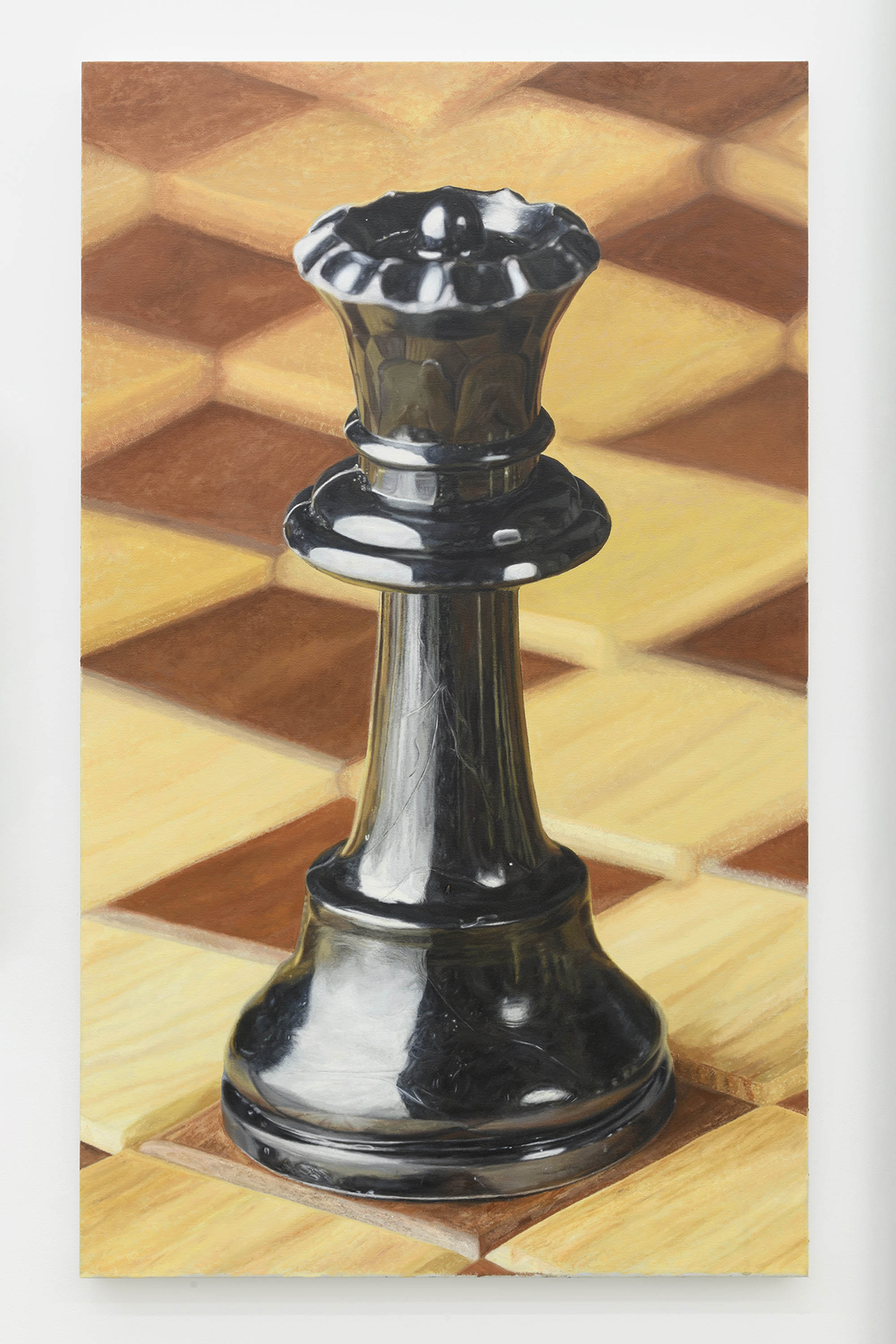

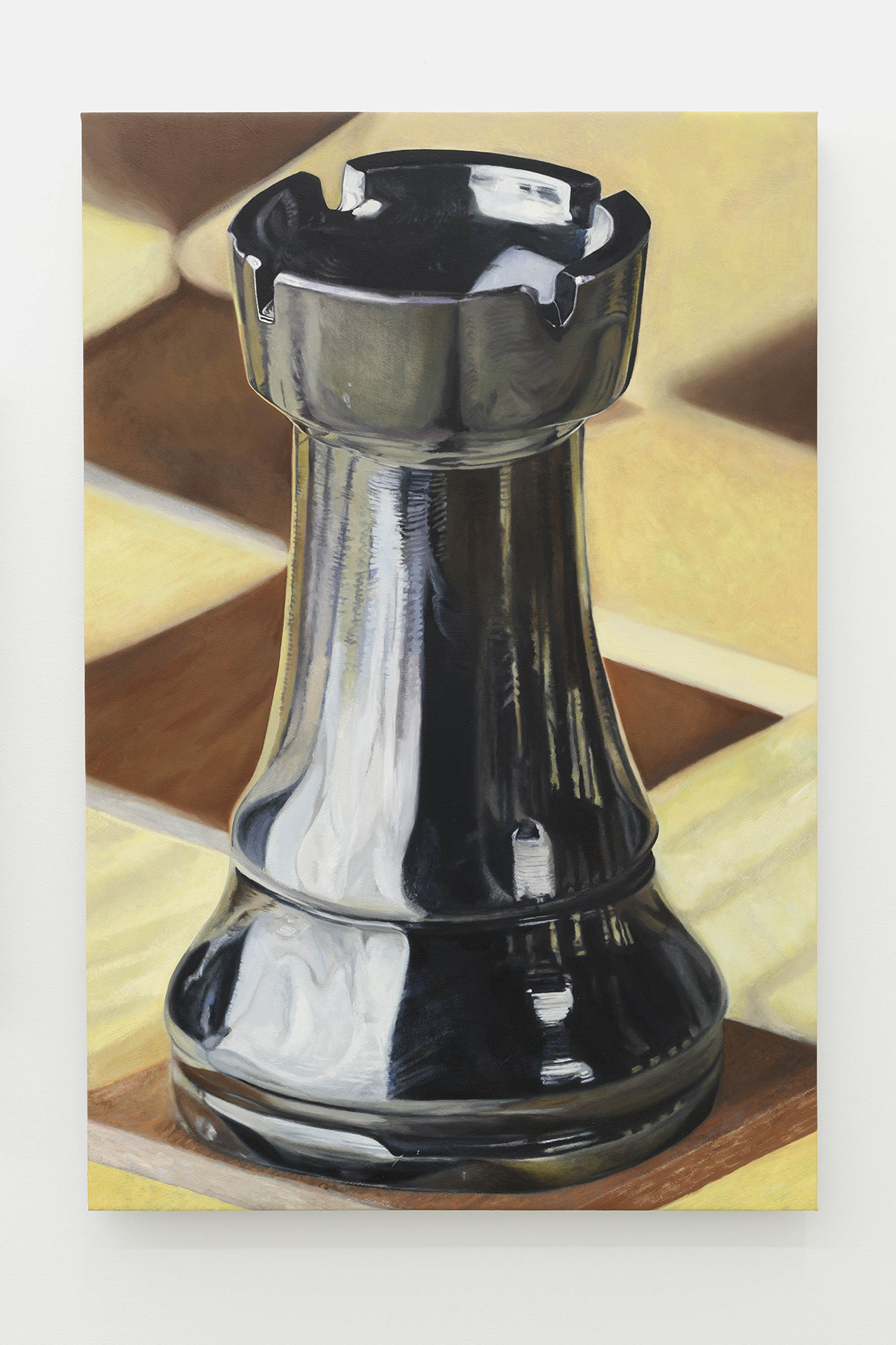

These are portraits of an army; whether in action or repose is not clear. In number they are replete like asymmetric warfare or like something that hasn’t happened yet.

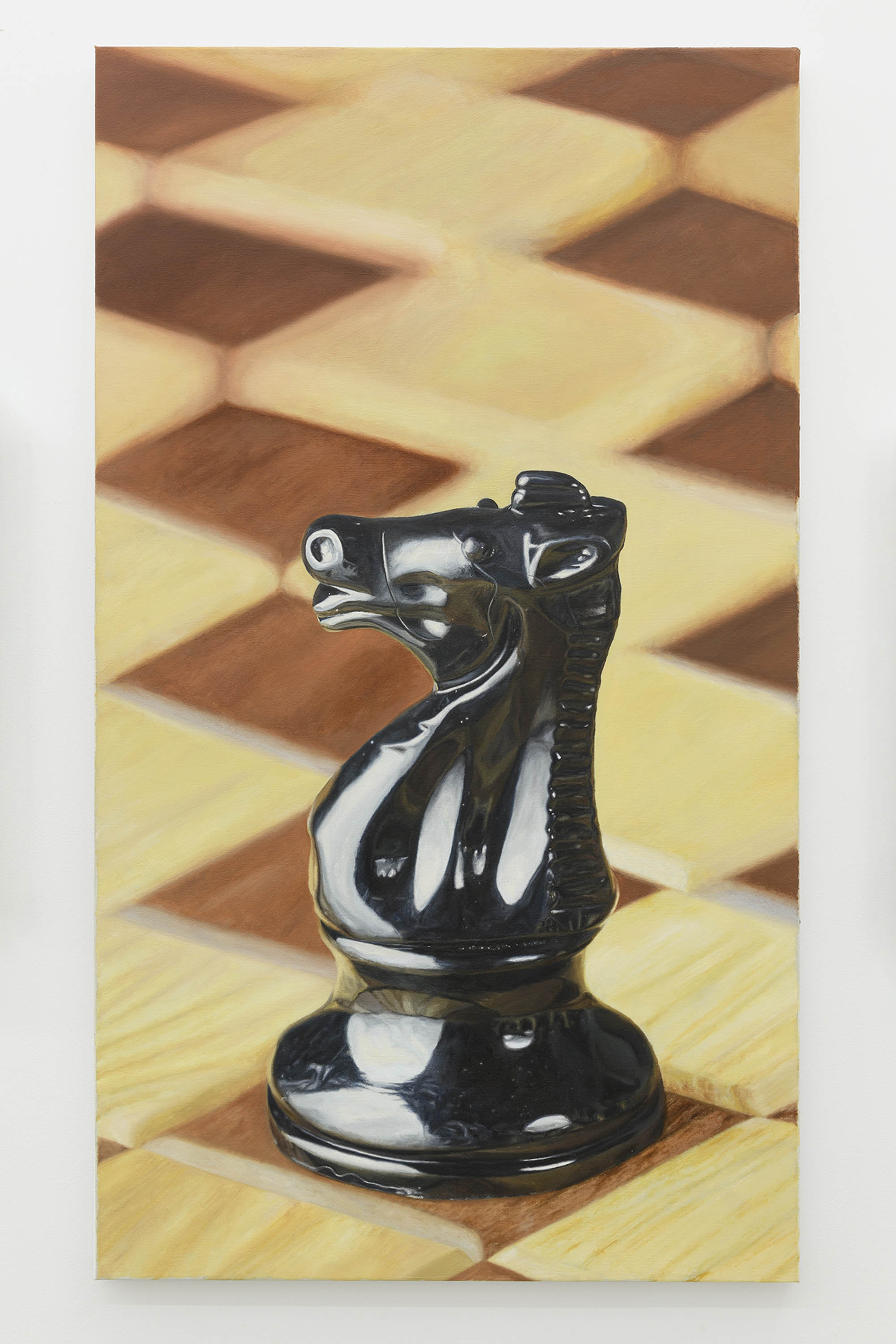

Something that has already happened, asymmetrically: black portraiture has been through an intense though not unprecedented revaluation in recent years, something like how coltan was an innocent rock before the rise of cellphones put it to work. Frenzied attempts to grasp recent history, aka the fluctuating symbolic fortunes of blackness and its relation to money and death, are the art-world equivalent of tantalum capacitors. Like those tiny vital phone parts, these preoccupations are always threatening to become obsolete—on a quantum-cultural level any art-world concern is entangled with obsolescence—but, at least when it comes to painting, the much-embellished question of Representation is inevitable and permanent. Hamishi Farah represents the aesthetic and political impasse presented by the hyper-object of black representation by painting black people exclusively given iconicity by world fame, for example a recent painting of Beyonce and Jay-Z in the sea and, now, these sixteen well-known figures. The simplicity of the gesture—we face the black pieces as the white side—contains a complicated wager about representation and play.

The art world is rife with belief in rules and stratagems: an elaborate social game of recognition, hierarchy and wealth. It is, like chess, an abstract game of tactics with only an extrinsic element of chance. To make this observation would perhaps only be to align Farah with some of the more arch and angry white conceptualists, but there are important differences of commitment. In his work, sadism is not a defensive subversion of a too-sincere belief in aesthetics but the basic problem of our era. Categories of law/rules of the game are a cover for an all pervasive sadism, the sadism of capital.

The circulation of blackness makes clear that the matrix of the market is white supremacy in action. Yet the point of Farah’s work is not to reveal its self-evidently difficult predicament but instead to make a somewhat tongue-in-cheek promise, the promise of a game: that conflict could be fun, funny and/or not that big of a deal. Sadism not reified but disarmed, dethroned. In this trickster-god guise, Farah’s work is a crypto-utopian comedy forged from the materials of dystopia.

In chess White always has an advantage because they are given the first move, and Black is left striving towards something a little bit humiliating like equality. But thankfully from the point of view of the chessboard, black and white is just a famous binary right up there with one and zero. Like binary code it’s a metaphor with real effects. These little guys are constrained to move according to their “nature”. That some shared accidents in the realm of the hereditary have turned us into living signs of captivity or freedom might be approximately the same mirror-stage process. Against blackness as a trap and for it as a breathtaking play with world history, Farah’s anti-representational representation energetically refutes the widespread myth that painting can make an image of a person.

These paintings present Farah’s side, the black side. Visitors to the gallery face the paintings as the white pieces face the black pieces on a board. The possible moves, playing as white: love, hate, leave, buy. It’s extremely serious and it’s just for fun.

To figure an audience as antagonistic pieces on an abstract board reminds of Farah’s previous playful provocations: What if Rachel Dolezal were a readymade? What if the body of Roberto Cavalli could be declared a nation state? Farah is, I think, the funniest artist working now, and therefore, of course, the most serious. Horror of one kind or another is reconfigured as absurdity, via the psychopathic mechanisms of the law. Living nightmares reappear as humorous dreams. Play is a way to live. But you cannot win.

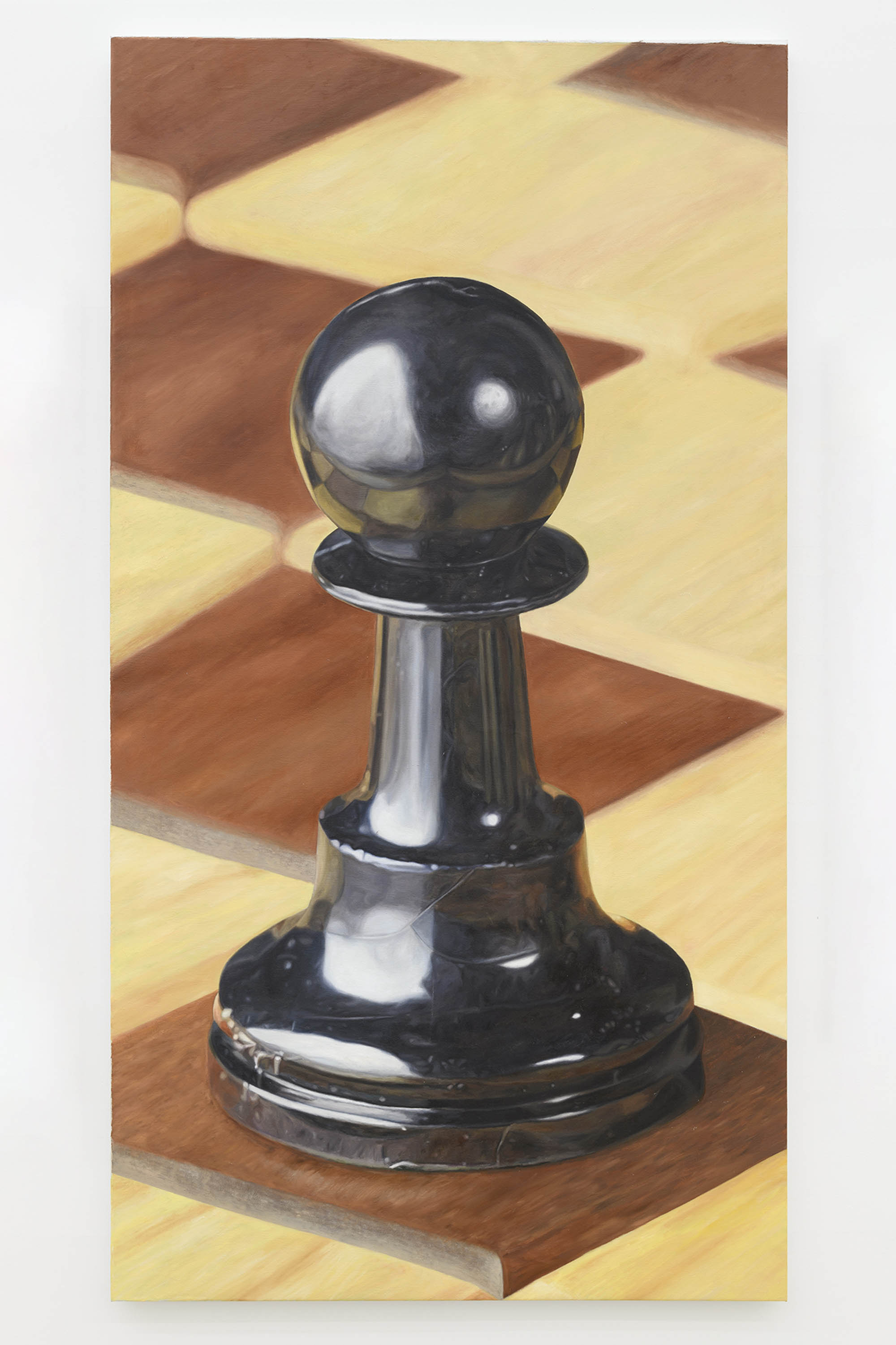

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

39 ½ × 18 ½ inches (100.33 × 46.99 cm)

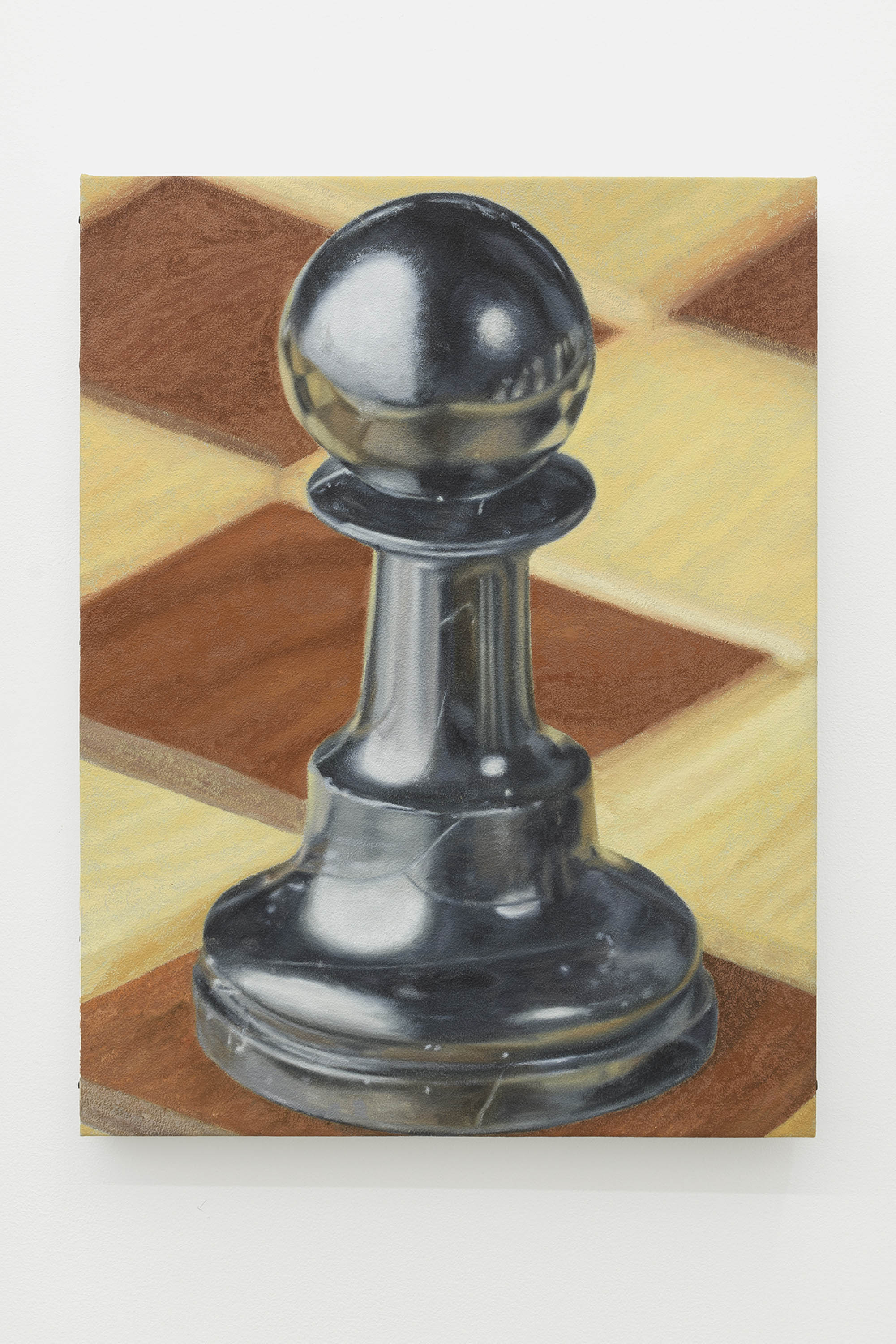

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

35 ¼ × 27 ⅜ inches (89.54 × 69.53 cm)

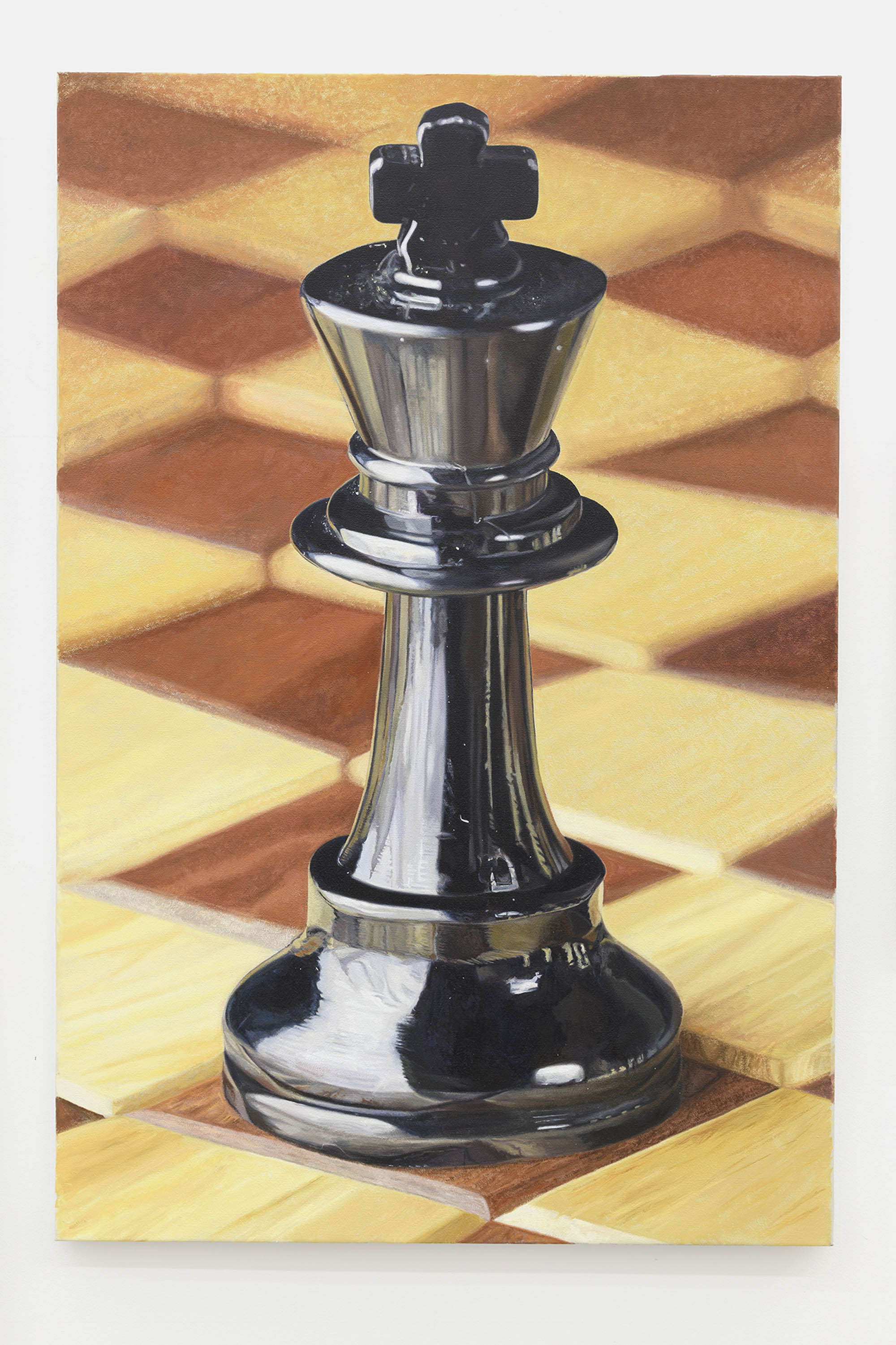

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

59 ¼ × 59 ¼ inches (150.5 × 150.5 cm)

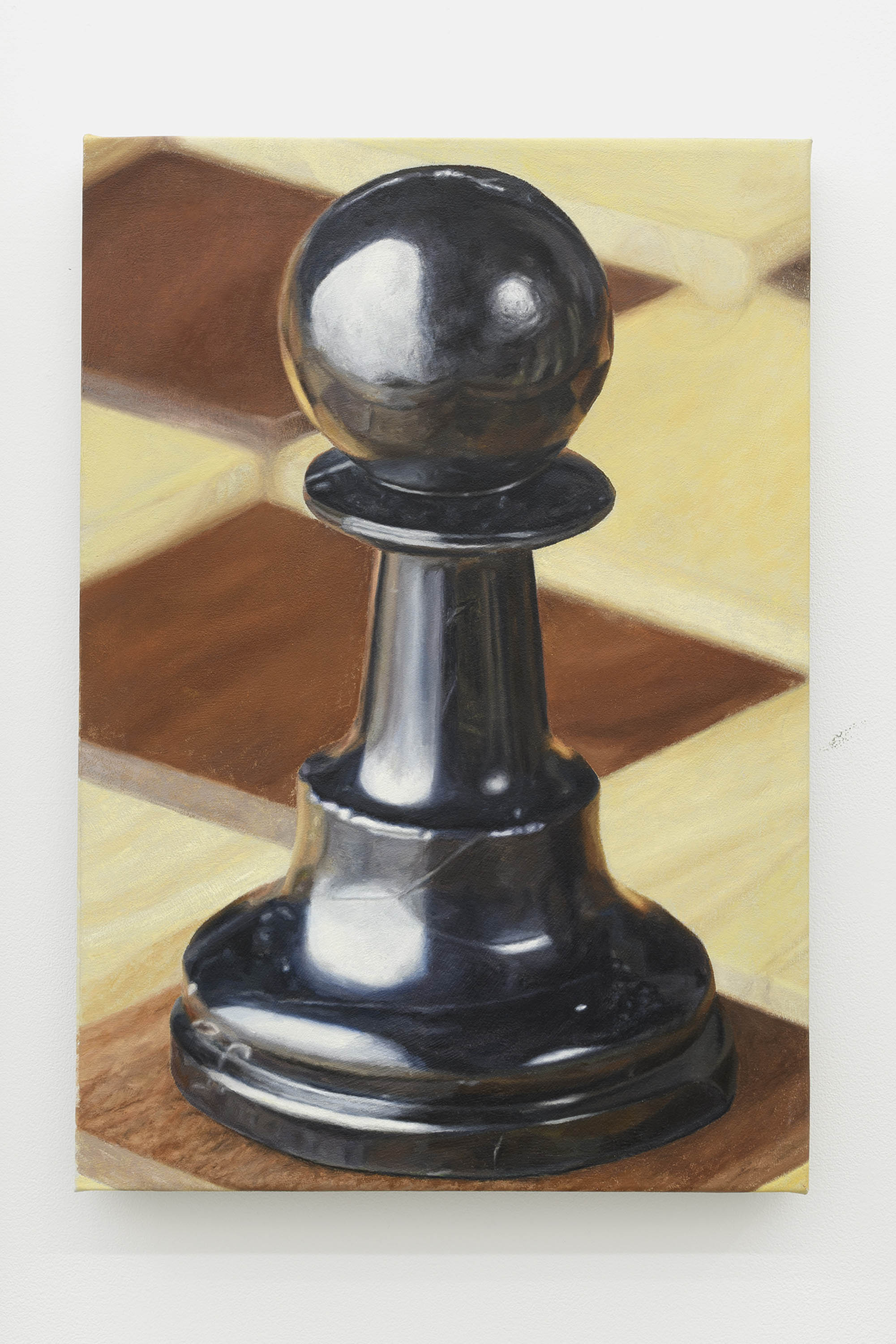

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

44 ½ × 32 ½ inches (113.03 × 82.55 cm)

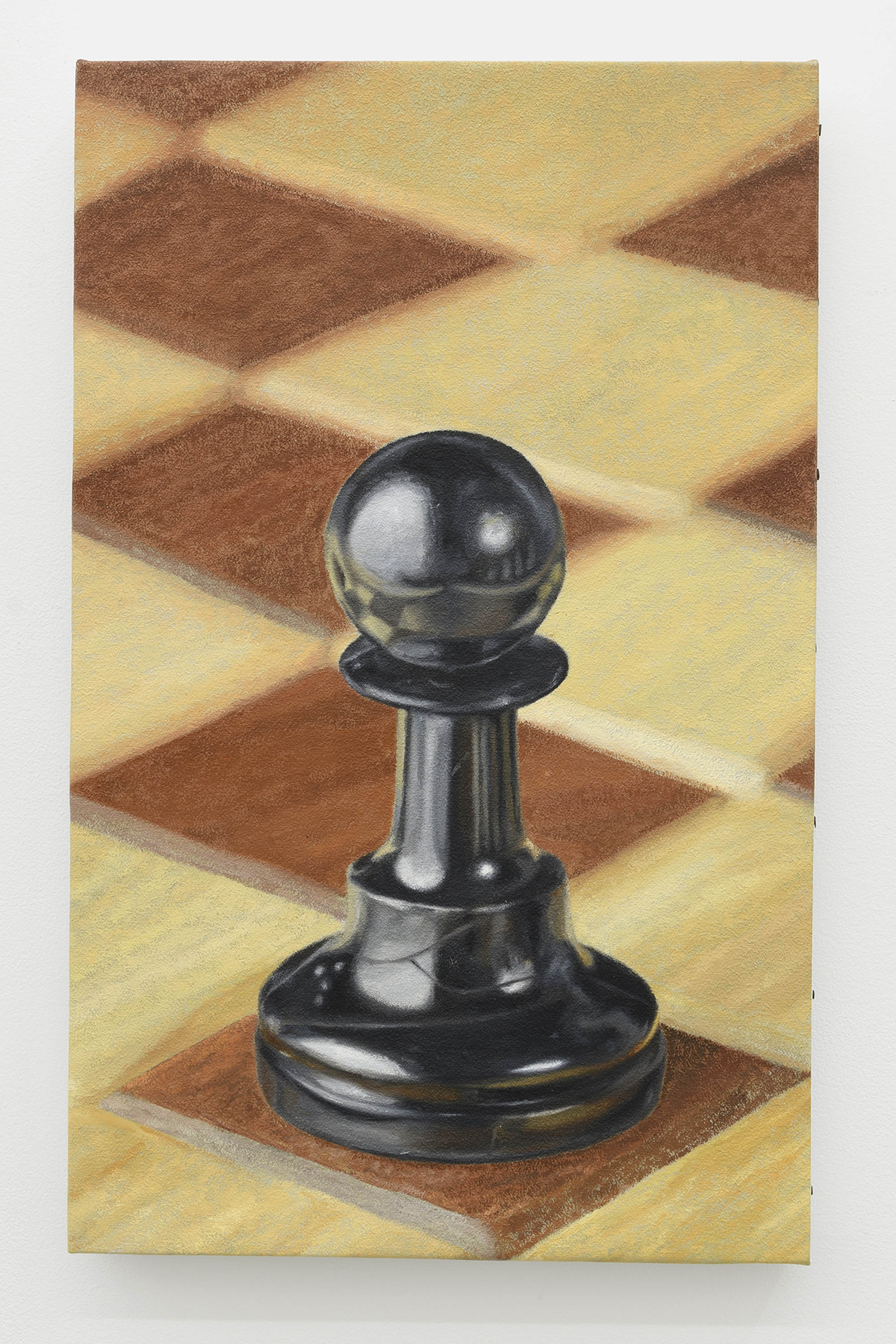

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

21 ⅜ × 16 ¼ inches (54.29 × 41.28 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

23 x 12 inches (58.42 x 30.48 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

25 ¼ × 7 ¼ inches (64.13 × 18.42 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

59 ⅞ × 35 ¾ inches (152.08 × 90.8 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

93 ¼ × 50 inches (236.85 × 127 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

51 ½ × 34 ½ inches (130.81 × 87.63 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

24 ¼ × 16 ¾ inches (61.60 × 42.55 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

75 ⅝ × 42 inches (192.08 × 106.68 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

22 ¼ × 13 ⅞ inches (56.52 × 35.24 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

55 ½ × 31 ¾ inches (140.97 × 80.64 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

21 ¼ x 16 ⅜ inches (53.975 x 41.59 cm)

Hamishi Farah

Pawn, 2023

Oil and pumice on linen

36 ⅝ x 24 ½ inches (93.0275 x 62.23 cm)